Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History: B

Filson Clubs Buys Papers of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell

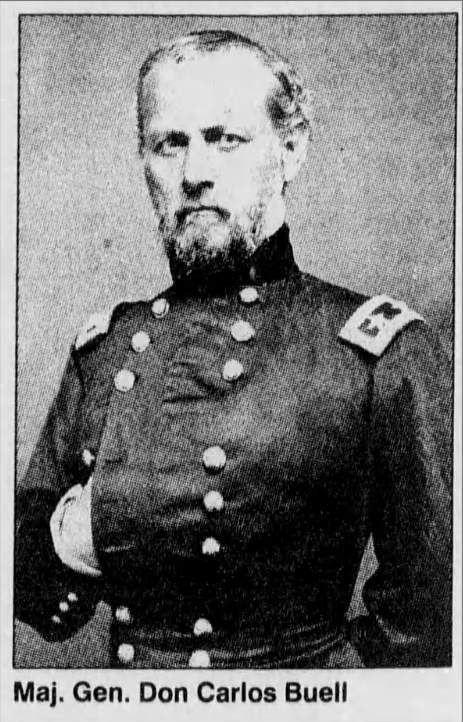

The frayed ends of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell's reputation have been gathered home to Kentucky, the site of their unraveling.

From one year beginning in November, 1861, Buell commanded the Union Army of the Ohio. His failure to crush Confederate forces after the Battle of Perryville in October 1862, along with earlier sources of dissatisfaction, cost him his command and ultimately ended his career.

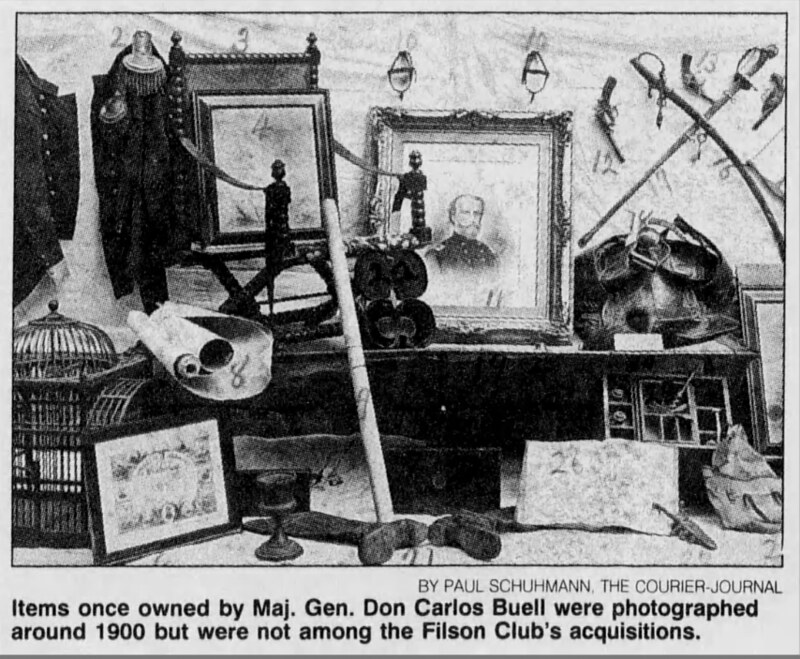

Tipped off by a source at Christie's auction house in New York City, The Filson Club Historical Society in Louisville recently bought Buell's personal papers from collateral descendants of the general. The papers - seven boxes full of letters and other documents, plus some maps, drawings and photographs - were on deposit for more than 30 years at Rice University in Houston, but Filson Club curators say they are nearly untouched.

“People that should have used them, would have wnated to use them, apparently did not know they were down there,” said James Holmberg, the club's curator of special collections.

Filson Club officials won't say what they paid for the Buell papers, but they are calling them the club's most important acquisition in years and a big plus for its Civil War collection, which is already rich in materials dealing with the Western campaigns.

Stephen Engle of Florida Atlantic University, who is writing the first biography of Buell, said he urged one of the two sisters who owned the papers to consider selling them to the Filson Club because of Buell's Kentucky connection and because the club would “do well by them.” Engle said only he and one doctoral student made extensive use of the papers while they were at Rice.

Holmberg said the papers help answer lingering questions about the unusually harsh treatment Buell received. The Union cause also got less out of Gens. John Charles Fremont, George McClellan, John Pope and Joseph Hooker than had been expected, but only Buell had his loyalty questioned.

A native of Ohioan who spent most of his youth in Lawrenceburg, Ind., Buell scraped through West Point, graduating in 1841. Engle said Buell was perpetually one demerit shy of expulsion.

In 1843, after taking part in the second Seminole War, Buell was court-martialed for assaulting a private. He was acquitted, but the case achieved widespread notoriety, with Gen. Winfield Scott weighing in against Buell and then-President John Tyler calling for an end to dissension over the case.

Buell's administrative abilities caught his commanders' attention during the Mexican War, during which he was twice breveted for bravery. Short, stocky and dour, he was a stern disciplinarian, but he also insisted on proper sanitation and commissary services for his troops.

He apparently had a playful side tinged with vanity: He liked to show off his strength by clasping his wife's; waist, holding her out in front of him and then lifting her to sit on a mantel.

Buell's reputation got a boost when his troops arrived at Shiloh in time to help turn the tide of that April 1862 battle. But authorities in Washington blamed Buell for the subsequent loss of Chattanooga to the Confederates, and they would have removed him from command before Perryville if Gen. George Thomas had not refused the assignment.

In the late summer of 1862, Confederate Gens. Braxton Bragg and Kirby Smith led separate columns into Kentucky. Thanks to Bragg's hesitancy, Buell arrived in Louisville in time to secure it from attack, then ventured out to find Bragg.

His forces blundered into Bragg's at Perryville on Oct. 8. Buell, injured by a fall from his horse the day before, was confined to an Army ambulance and was unaware a battle was in progress until late in the day.

The Confederates drove Buell's troops from the field, but badly outnumbered, they were forced to withdrawn into Tennessee. Buell's; failure to use his army's superior size to pursue and destroy Bragg renewed the clamor for his removal. He damaged his case further by disobeing orders to advance into East Tennessee.

Engle said Buell, like McClellan, also refused to adapt to the shifting politics of war. A one-time slaveowner, Buell persisted in returning runaway slaves to their masters, and he was reluctant to seize Confederate property even after Congress passed the Confiscation Act in July 1862.

Buell was removed from command on Oct. 24, 1862. Incensed that some politicians were branding him a traitor, he called for an investigation of his conduct.

A commission spent five months weighing the evidence. It made no findings of fault, but Buell was never again offered command of an army, and he resigned his commission in June 1864.

A letter, now at the Filson Club, that Buell wrote in July 1864 to Adjutant Gen. Lorenzo Thomas describes his motives for leaving the service. It also helps explain why Buell's superiors in Washington welcomed his departure.

“The impulses of most men would approve my course in this matter, if it even rested on no other ground than a determination not to acquiesce in any measure that would degrade me,” Buell wrote.

“But I had a higher motive than that. I believed that the policy and means with which the war was being prosecuted were discreditable to the nation, and a stain upon civilization; and that they would not only fail to restore the union, if indeed they had not already rendered its restoration impossible, but that their tendency was to subvert the institutions under which the country had realized unexampled prosperity and happiness; and to such a work I could not lend my hand.”

After leaving the Army, Buell leased Airdrie, an estate in Muhlenberg County, Ky. He operated a mine there and, after it went bankrupt, was named a pension agent in Louisville.

He died at Airdrie in 1898. The house burned a few years later.

Unlike the letters of Sherman, McClellan, and Ulysses Grant, Buell's convey little personal feeling, Engle said. Still, he said, the papers offer valuable information on the war in the West and on Federal commanders.

Filson Club curators plan to make the papers available to researchers in mid-1998. Engle feels that, taken with other materials on Buell, they show that the officer who once slashed a private's ear with his sword in the end proved too chivalrous for the Civil War.

“I think the war outgrew what he had to offer,” Engle said. Northern aims, he said, came to include destroying slavery and the society based on it - “and that was just not the kind of war Buell was willing to wage.”

Source: Jennings, Michael. “Filson Clubs Buys Papers of Gen. Don Carlos Buel.” The Courier-Journal [Louisville, KY], 22 Dec 1997, Indiana Edition, p. 4.

Updated July 13, 2022