Excerpt from Blue Ridge Country by Jean Thomas, Copyright 1942

THE SILVER TOMAHAWK

Submitted by Glen Haney

In Carter County, Kentucky, there is a legend which had its beginning

long ago when Indian princesses roamed the Blue Ridge, and pioneers'

hopes were high of finding a lost silver mine said to be in caves close

by.

Morg Tompert loved to tell the story. As long as he lived the old fellow

could be found on a warm spring day sitting in the doorway of his little

shack nearly hidden by a clump of dogwoods. A shack of rough planks that

clung tenaciously to the mountain side facing Saltpeter, or as it was

sometimes called--Swindle Cave. The former name came from the deposit of

that mineral, the latter from the counterfeiters who carried on their

nefarious trade within the security of the dark cavern.

As he talked, Morg plucked a dogwood blossom that peeped around the

corner of his shack like a gossipy old woman. "See that bloom?" He held

it toward the visitor. "Some say that a Indian princess who was slain by

a jealous chieftain sopped up her heart's blood with it and that's how

come the stains on the tip of the white flower. There have been Indian

princesses right here on this very ground." Morg nodded slowly. "There's

the empty tomb of one--yes, and there's a silver mine way back yonder in

that cave. They were there long before them scalawags were

counterfeiting inside that cave. Did ever you hear of Huraken?" he asked

with childish eagerness. Morg needed no urging. He went on to tell how

this Indian warrior of the Cherokee tribe loved a beautiful Indian

princess named Manuita:

"Men are all alike no matter what their color may be. They want to show

out before the maiden they love best. Huraken did. He roved far away to

find a pretty for her. That is to say a pretty he could give the

chieftain, her father, in exchange for Manuita's hand. He must have been

gone a right smart spell for the princess got plum out of heart, allowed

he was never coming back and, bless you, she leapt off a cliff. Killed

herself! And all this time her own true love was unaware of what she had

done. He, himself, was give up to be dead. But what kept him away so

long was he had come upon a silver mine. He dug the silver out of the

earth, melted it, and made a beautiful tomahawk. He beat it out on the

anvil and fashioned a peace pipe on its handle. He must have been proud

as a peacock strutting in the sun preening its feathers. Huraken was

hurrying along, fleet as a deer through the forest, his shiny tomahawk

glistening in his strong right hand. The gift for the chieftain in

exchange for the princess bride. All of a sudden he halted right off yon

a little way. There where the stony cliff hangs over. Right there before

Huraken's eyes at his feet lay the corpse of an Indian lass, face

downward. When he turned the face upwards, it was the princess. Princess

Manuita, his own true love. His sorryful cry raised up as high as the

heavens. Huraken was plum beside himself with grief. He gathered up the

princess in his arms and packed her off into the cave. Her tomb is right

in there yet--empty."

Old Morg paused for breath. "Huraken kept it secret where he had buried

his true love. He meant to watch over her tomb all the rest of his life.

Then the chieftain, Manuita's father, got word of it somehow. He vowed

to his tribe that Huraken had murdered his daughter in cold blood. So

the chieftain and his tribe set out and captured Huraken. They bound him

hand and foot with strips of buckskin out in the forest so that wild

varmints could come and devour his flesh and he couldn't help himself.

He'd concealed his tomahawk next to his hide under his heavy deerskin

hunting coat. But the spirit of the dead princess pitied her helpless

lover. Come a big rain that night that pelted him and soaked him plum to

the skin. The princess had prayed of the Rain God to send that downpour.

It soaked the buckskin through and through that bound Huraken's hands

and feet and he wriggled loose. Many a long day and night he wandered

away off in strange forests, but all the time the spirit of his true

love, the princess, haunted him. He got no peace till he came back and

give himself up to the chieftain. Only one thing the prisoner asked.

Would they let him go to the cave before they put him to death? Now the

Cherokees are fearful of evil spirits. When they took Huraken to the

mouth of the cave they would go no farther. 'Evil spirits are inside!'

the chieftain said, and the rest of his tribe nodded and frowned. So

Huraken went into the dark cave alone. From that to this he's never been

seen. And the corpse of the Princess Manuita, it's gone too. Her empty

tomb is in yonder's cave. Not even a crumb of her bones can be found."

Old Morg Tompert reflected a long moment. "I reckon when Huraken packed

the princess off somewhere else her corpse come to be a heavy load. He

dropped his silver tomahawk that he had aimed to give the chieftain for

his daughter's hand. It lay for a hundred year or more--I reckon it's

been that long--right where it was dropped. Off yonder in Smoky Valley

under a high cliff some of Pa's kinfolks found it. A silver tomahawk

with a peace pipe carved on its handle. Pa's own blood kin, by name, Ben

Henderson, found that silver tomahawk but no living soul has ever found

the lost silver mine. There's bound to have been a mine, else Huraken

could never have made that silver tomahawk. Only one lorn white man knew

where it was. His name was Swift. But when he died, he taken the secret

of the silver mine to the grave with him. Swift ought to a-told some of

the womenfolks," declared old Morg, still vexed at the man Swift's

laxity though his demise had occurred ages ago. "Swift ought to a-told

some of the womenfolks," old Morg repeated with finality.

Searching for Swift’s Lost Silver Mines

by: Brook and Barbara Elliott

John Swift’s journal may be more than 200 years old,

but Kentuckians are still searching for his lost silver mines and cache that have never been found

“It’s near a peculiar rock. Boys, don’t ever quit looking for it. It is the richest thing I ever saw.”

With those deathbed words, uttered about 1800, John Swift set off the longest running treasure hunt

in Appalachia. A hunt that continues today.

According to the legend, John Swift, of Alexandria, Virginia, discovered several silver mines in the hills of eastern Kentucky.

His first finds were in 1760, and there were several others. In addition to the mines themselves, there are,

so it is said, caches of silver coins and ingots waiting to be found.

It started when Swift befriended a man named George Munday, a Frenchman captured at the Battle of

Fort Duquesne during the French and Indian War. Munday had discovered a vein of silver somewhere on the

headwaters of Big Sandy Creek. But the Shawnee attacked, killing his father and brothers and making him a prisoner.

Munday remained a captive of the Shawnee for three years, during which time he was forced to help mine

silver in several places. Because Swift had helped him, he agreed to guide him to these Indian silver mines.

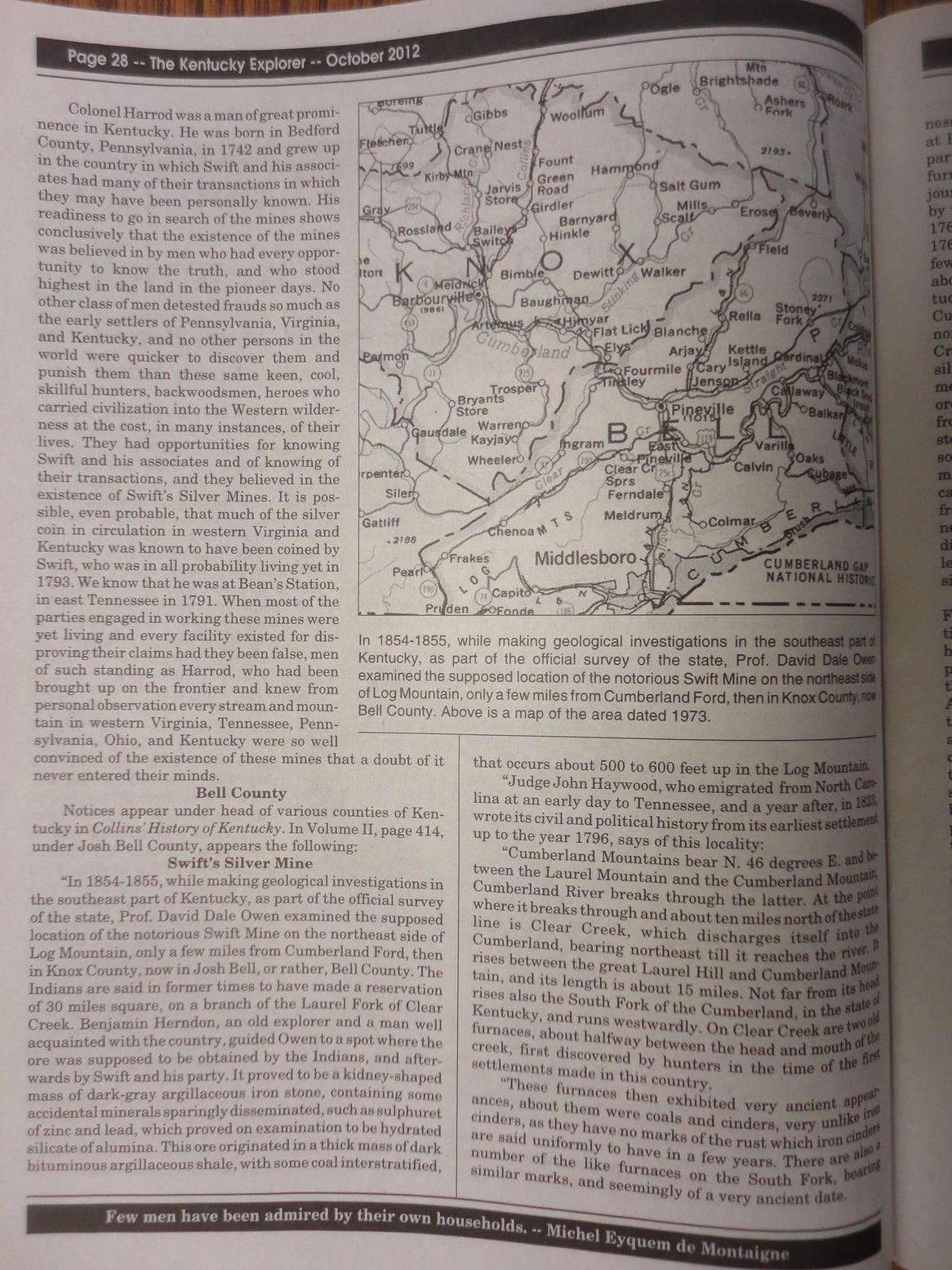

On the first expedition, Swift says in his journal, “After crossing Big Sandy Creek, near its headwaters,

and continuing west for a considerable distance, we located three of the mines.” They then traveled

southwesterly, following a great ridge, where they found other mines near a large river.

On subsequent explorations, Swift and his crews uncovered several other mines, and established smelters

where they refined it and cast it into coins of the era. Ironically, such coins—some of which have been

recovered—contain more silver than the issued specie of the day. Whether John Swift and his crew actually

cast these coins remains to be seen. Such counterfeiting was fairly common in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Swift went to London, England, to raise capital for developing the mines. While there he was outspoken in

his support of American independence, and was imprisoned for his views. He spent 10 years in jail,

losing his eyesight during that period.

Aged, infirm, and blind, he returned to western Appalachia to rediscover his mines. Using a journal he had

kept of his adventures, and hiring local people to guide him based on his remembered landmarks, he spent

the rest of his life trying to find his lost silver mines.

He never did. But to help support himself, he sold various copies of his journal, broadsides, and maps—all

of which held clues to the lost mines. At least 36 versions of the journal were produced until his death,

along with 29 known treasure maps. Using those heirlooms and other reference works, thousands of treasure

seekers have spent the past 200 years searching for the lost mines in what is one of the most enduring,

and one of the most endearing, legends of the southern hills.

They come merely with an old map and hope. And they come with metal detectors and the results of deep

research. And they sometimes come with great financial backing. In the late 1990s a major search went on

headquartered in Elkhorn City. The organizer was said to be backing this serious treasure hunt to the tune of $150,000.

What keeps them searching? Through the years, there have been silver finds resulting from the clues found

in Swift’s journals, and by using the signs and symbols he left carved on rocks and trees. There have been

too many of these finds—which include ingots, coin molds, and caches of silver coins, silver ingots, and

shaped artifacts—to dismiss the legend out of hand. This despite the fact that geologists all seem to agree

there is no silver of any consequence in the Kentucky hills.

Former newspaperman Michael Steely, a great collector of Swift lore, details some of these finds in his

book, Swift’s Silver Mines and Related Appalachian Treasure:

•A Kentucky man has a mostly silver ax head, or wedge, he found near an old smelter.

•An Ohio man has several “fingers” of silver he found while searching for the mines.

•Several Spanish coins from the Swift era were found in North Carolina, setting off a small silver rush.

Steely himself remained skeptical until he found a large, silver spearhead at a site he believed to be

indicated by some of the Swift rock carvings. He showed me that artifact, which has been appraised as 85%

silver (the rest is ash and impurities). It is obviously crudely forged, from a single lump of silver.

Most recently, using the symbols at the so-called Lakely stone carvings, near the town of Frakes, a man

found a cache of seven small silver ingots. The Lakely carvings, which are supposedly coded directions to

a Cherokee hoard of gold and jewelry, rather than to the Swift mines, have been used by treasure hunters for years.

Reading copies of John Swift’s journals, you are struck with the detail and precision of his descriptions.

Trouble is, the geology described fits many places in eastern Kentucky and surrounding areas.

For instance, Roy Price, one of the foremost Swift treasure seekers and collectors of Swift lore in the

country, took me to a spot near Jellico, Tennessee. There’s a naturally carved Indian head in the cliff,

and a lighthouse nearby, that seem to be perfectly described by Swift. “A treasure map, widely circulated

in the last century, brought many treasure hunters here,” Price told me, “and is still being used by hunters today.”

The site is easy to find. Just take U.S. 25W south about five miles from Jellico, and the cliff is across the river on your left.

Nobody has found anything at the Jellico site. But by the same token, nobody has discovered silver near a

similar site, which also matches the description, found near the entrance to Natural Bridge State Park,

here in Kentucky. If you visit the park, stop as you turn in to the Hemlock Lodge entrance and look to the

cliff line on your right. You’ll see the Indian Head Rock, and the lighthouse (named Owl’s Window), just under it.

While many of the sites, especially those that have rock or tree carvings, are closely held secrets, just

as many are easily accessible to the general public. You don’t even need a treasure map to find them.

General-interest publications often guide you to the possible location of the mines.

So, “go to it, boys. If you find this silver mine, let me know—and we will celebrate.”

Searching For Swift’s Silver Mines

Although many of the supposed sites of Swift’s silver mines and lost cache are closely guarded secrets,

there are several public sites that are easily accessible. Here are some of them:

Breaks Interstate Park. The Towers, a prominent landmark formed in a horseshoe bend of the Russell Fork,

is said to be described in several versions of Swift’s journal.

Jenny Wiley State Park. In the captivity story of Kentucky heroine Jenny Wiley, she talks about

smelting silver with her captors. The well-described site is probably not in the park, but you might

discover it along the 180-mile Jenny Wiley trail.

Carter Caves State Park. There are several sites at Carter Caves associated with the lost silver mine,

X Cave and the Saltpeter Cave among them. Saltpeter Cave is also known as a counterfeiter’s cave, and is

supposedly the site of a French silver mine that Swift identifies in his journal.

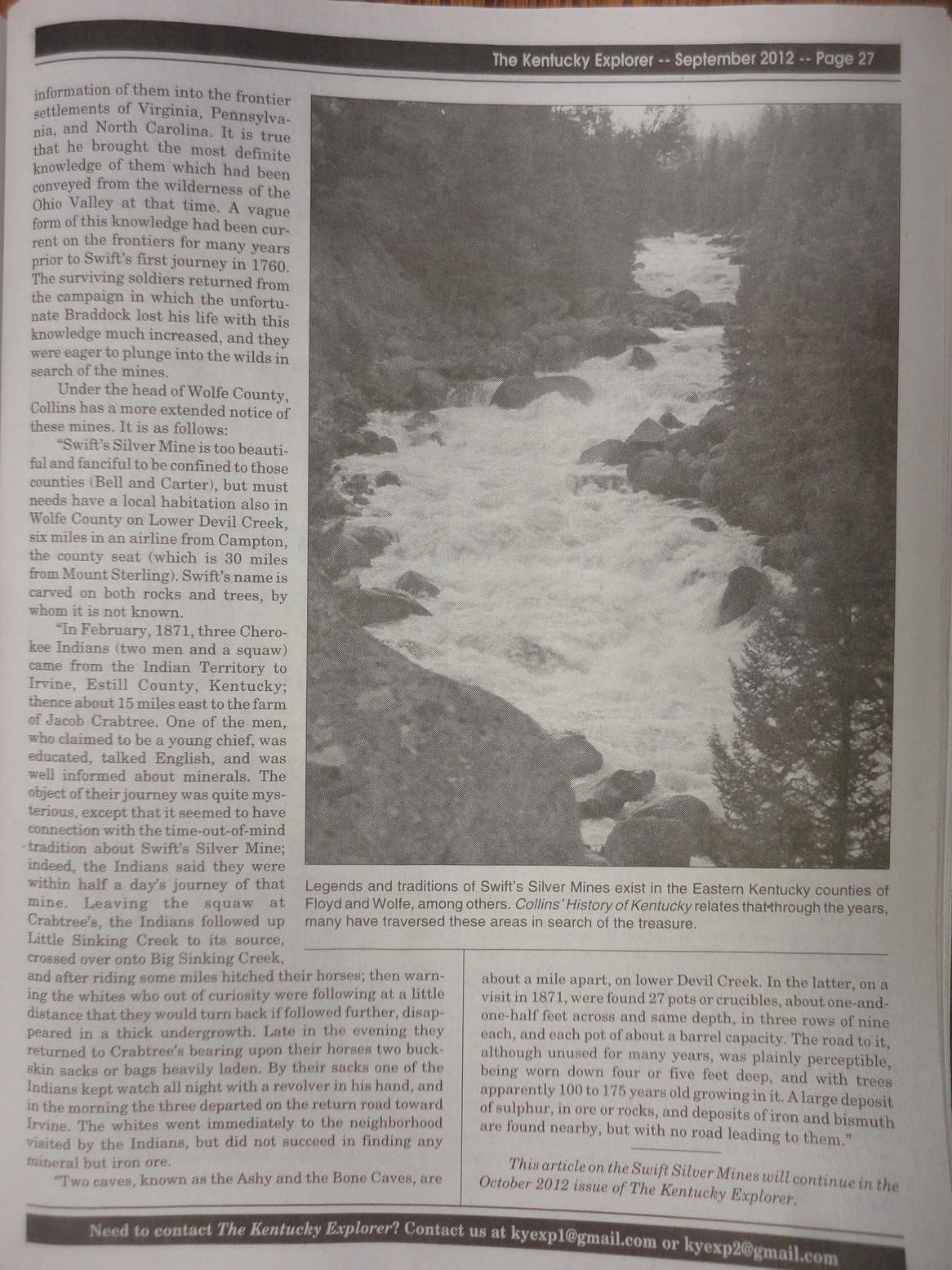

Red River Gorge. Red River Gorge is the center of the John Swift legend, and was the last area he searched

before his death. Among the many possible locales are Rock Bridge, on Swift Camp Creek; Swift Silvermine Arch;

and Becky Timmons Arch.

Cumberland Gap. Mentioned by Swift as “the Great Gap,” it’s also where the Spurlock family—who settled in

Kentucky specifically because of the lost mine—began their searches.

Pine Mountain State Park. Most searchers believe the mines are somewhere on Pine Mountain—called

Laurel Mountain by Swift. Although they could be anywhere in the 125-mile-long mountain, the state park is

as good a place as any to begin your search.

Cumberland Falls State Park. The Renfro family settled here, also in search for lost silver mines.

Big South Fork National Recreational Area. The 105,000 wilderness acres of the Big South Fork are

associated with both the Swift and lost Cherokee silver mine legends.