Poverty drove Olive Hill residents to Mansfield for work 60 years ago

Written by Willie Davis, Guest columnist

Submitted by: Mike Barker - mikebarker1950 @ hotmail.com

A scene from downtown Olive Hill, Ky., circa 1958. / Submitted Photo

First article of the series

Dec. 10, 2011

Poverty drove Olive Hill residents to Mansfield for work 60 years ago

Written by Willie Davis, Guest columnist

Submitted by: Mike Barker - mikebarker1950 @ hotmail.com

A scene from downtown Olive Hill, Ky., circa 1958. / Submitted Photo

MANSFIELD -- Olive Hill, Ky., and Carter County Appalachians who sought work in Mansfield and Richland County in the 1940s, '50s and '60s were often culturally stereotyped. Numerous Mansfield residents classified them as backward hicks, rednecks and hillbillies. People said they beat their kids, friends, neighbors and dogs; they were white, racist and little more than cheap labor. A deeper read could reveal a better understanding of those people who made north central Ohio home and have left two more generations here as their legacy. People, like birds, migrate. Any Richland County resident still clinging to the perception the Olive Hill folk are second-class citizens should know one undeniable truth. Richland and Carter County, Kentucky, are two peas in a pod. Both have wild and woolly histories, both are victims of people migration, and both are trying to fight back to protect and regrow the quality of life that once flourished. A few years ago, I found myself in downtown Olive Hill, Ky. Railroad Street, the main drag, was decimated. Windows were boarded up. The scene is eerily similar here. Recently I found myself by the old Westinghouse plant in Mansfield. Decimated. Windows boarded up. What irony, I thought. The migration flu bug that bit Carter County in the 1940s and '50s bit Richland County in the 1970s and 80s. There have been three major migrations in our country's history. The first great migration was Manifest Destiny, the philosophy that United States citizens had the God-given right to expand from the Atlantic to the Pacific. People started moving west and didn't stop until the U.S. was a bicoastal nation. Our second great migration grew out of the Depression and continued after World War II. From the dust bowls of the Midwest people went west, many to California. From the South they went north and joined other northerners who clustered around the industrial cities. The Carter County to Richland County migration was just a small slice of this second migration. For two decades, about 400,000 Kentucky residents migrated to the industrial north for work. Carter County and Olive Hill had fallen on hard times. Meanwhile, from Pittsburgh to Chicago, the jobs were plentiful and the pay was good. The third great migration is now taking place. People from the South are returning to their roots as the industrial work in the north has moved south or disappeared off shore. Millions of baby boomers will not spend their retirement years above the Mason-Dixon Line. They are opting for warmer climates and a simpler life in the South. The downside to this third great migration is being felt politically and economically now. Ohio has lost national representation in Congress and statewide revenue. The gain for the South has been an increase in revenue but also increased pressure on the infrastructure, social services and health care. Richland County hired my family. I was born in Olive Hill, Carter County, Ky. Mansfield has been home since 1959. I was 12 and my brother was 10 when our family joined the Kentucky mass exodus. Our father had been making Carter County bricks for 33 years, minus his two years of World War II service, before hiring in and working 12 years at Borg-Warner. Our mother had taught school for 17 years in Kentucky before starting a 30-year teaching career in Ontario. The ugly truth is it has been acceptable by many in our society to make fun of other cultural groups. I blame "Li'l Abner" and "The Beverly Hillbillies" for perpetuating the hick perception, but that's just a humor wink. It never surfaced for my brother and me. We didn't get into rock fights with the locally bred school bullies or run home crying to our parents about how mean everyone was to us because of our Kentucky heritage. Everyone moved along with their life just fine, thank you.

Second article

Dec. 11, 2011

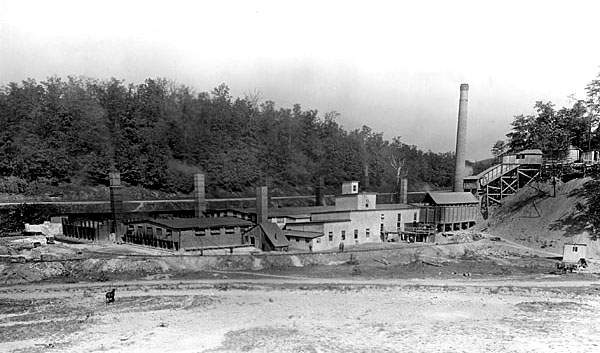

Variety of mines fueled growth of Olive Hill

Carter County was once a prosperous, blue-collar workhorse county, full of proud, self-reliant, independent, patriotic people with strong family values. Carter County was legislated into existence in 1838, with a population of around 2,300. It has two incorporated cities, Grayson and Olive Hill. However, the Carter County story is not one of demographics and numbers, but of the rise and fall of its natural resources before, during and after the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was an economic revolution. It started in Great Britain in the late 1700s, spread throughout Europe, and then found a home in America between 1820 and 1870. The gold of Carter County was its raw materials. The secret behind the county's economic success was the people's ability to find raw material, extract it, make something out of it and do it all over again. For more than 100 years, Carter County's raw materials of iron ore, fire clay, coal, timber and limestone helped fire our American Industrial Revolution, which, in turn, helped fire the United States' economic growth. But, eventually, each fire burned out. Iron ore first Iron ore was Carter County's first claim to natural resource fame. Carter iron ore furnaces, part of the 100-mile Hanging Rock Iron Ore Region, helped produce most of the iron ore in the nation from 1825 through 1885. Thousands of pioneer pots and pans and munitions from Antietam to Appomattox were shaped from Carter's iron ore furnaces. When the big city steel blast furnaces burst onto the scene, Carter County's iron ore fire extinguished. Then fire clay Iron ore footprints in the Industrial Revolution were small in comparison to those left by Carter County's fire clay. Steel-making blast furnaces of the Industrial Revolution reached temperatures of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. These steel furnaces needed to be lined with something that could withstand this intense heat. The answer to keeping molten steel from burning up a blast furnace was fire bricks made from fire clay, a natural resource not readily found in the 1870s. The only fire clay available was located in small pockets in the east. By the 1880s, the Industrial Revolution had created a need for more steel, which created the need for more furnaces. More locomotives on more tracks meant more fire boxes. Anything produced with high heat needed fire bricks. Carter County delivered big time. A large deposit of fire clay was discovered in a 400-square-mile area around Olive Hill. This clay was nearly perfect for making the needed bricks, as it had different grades and textures, from gray to white and grainy to more plastic -- and there was a lot of it. This fire clay discovery in the Olive Hill District became a shot-in-the-arm for America's Industrial Revolution, Carter County and Olive Hill. The timing could not have been better. Soon, Olive Hill District fire bricks began coating the insides of blast furnaces, kilns and fireplaces throughout the Midwest, especially in the hotbed steel-making cities of Pittsburgh and Cleveland. Olive Hill fire bricks were used by railroad companies for their locomotive fire boxes, power plants, potteries, coke ovens and anywhere else high temperatures were encountered. Olive Hill fire bricks were eventually shipped throughout the world. Big and small mines began dotting the Carter County landscape. In all there were about eight brick plants constructed around the turn of the century. At their height, these brick plants produced an average of 500,000 nine-inch bricks per day. One source calculated this amount of bricks to require 2,000 tons of fire clay, which then filled 50 train carloads of fire bricks. Unfortunately, the fire clay industry in the Olive Hill District was destined to end. That end started materializing in the 1950s, with changes in the steel industry that practically eliminated the need for fire bricks. Oxygen-induction furnaces were invented and quickly became the norm, replacing the need for Olive Hill's fire bricks. Plus, so much of the fire clay had already been mined over the past five decades, that more time would have certainly ended the fire brick run. Again, another Carter County fire was gone. Black heat Coal was discovered in Kentucky in 1750, and has been mined there ever since. Kentucky is one of the top five coal-producing states in the country, with more than 400 coal mines as of 2010. Coal was mined from Carter County in three major intervals. The brickyards needed coal to heat the kilns that made the fire bricks. The miners often mined the fire clay and coal underground at the same time from the same mine. A second boom came during World War II to feed the furnaces that made the ships, planes and tanks. A third boom occurred in the 1970s with the advent of strip mining. Although there are now more than 20 Kentucky counties mining the Eastern coal field, Carter County is not among them. Better coal that was easier to mine was found elsewhere, and falling prices, labor disputes and increased government regulations all helped end Carter County's coal production. Yet more than 1.7 billion tons of coal were extracted from Carter County from the mid-1800s to 1993. Again, the fire was out. Other natural resources Saltpeter, or sodium nitrate, was mined during the War of 1812 to make gun powder. This resource was found in caves in the northeast part of Carter County. There was also an abundance of timber and limestone in Carter County. Logging and saw milling was always a prominent industry, beginning with the explosion of the railroad companies. A lot of railroad cross-ties are made with timber from Carter County trees. And limestone mining hit its high point in the 1920s.

Third article

Dec. 12, 2011

Olive Hill was trading post in its early days

The Haldeman Brick Plant was one of eight in the Olive Hill Fireclay District.

This facility knocked out about 40,000 bricks per day. / Submitted photo

MANSFIELD -- Olive Hill, Ky.'s roots can be traced back to the early 1830s as a trading post. It was a stagecoach stop along current highway U.S. 60 and the future Midland Trail, which eventually connected Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles. Olive Hill was originally on a hill overlooking Tygarts Creek, named after Michael Tygart, an early Kentucky explorer. As the story goes, Olive Hill was named by Elias P. Davis for his friend Thomas Oliver, the oldest resident in the area. Davis named the village Oliver Hill. And, as the story goes, the name was just too hard to roll off the tongue easily, so villagers just shortened it to Olive Hill. To confuse matters even more, the upcoming railroad had not planned to chug its way up that hill. So, citizens decided to move from the "hill" to the "valley" and relocate near the scenic Tygarts Creek and new railroad tracks. Olive Hill is not really on a hill, and its name is really missing an "r" because, like the Holland Bridge in World War II, it was a syllable too far. Kentucky has produced a lot of notable people. Two people stand out originating from Olive Hill: Tom T. Hall and Matthew Sellars. Hall is a country music singer and songwriter who has penned 11 No. 1 hit songs. Hall has written songs recorded by Johnny Cash, George Jones, Loretta Lynn, Waylon Jennings, Alan Jackson and Bobby Bare. Sellars was an inventor who conducted early aeronautical research and made the first powered airplane flight in Kentucky in 1908. He invented and patented the retractable landing gear. He has been hailed as one of America's great flying men along with Orville and Wilbur Wright. In general, the railroad and all its depots were the spark for the area's population and economic growth for many years. In Olive Hill's heyday, the Chesapeake and Ohio passed seven trains a day through Olive Hill, with additional stops at small depots east and west of town. President Truman even made a "whistle-stop" campaign appearance in Olive Hill before defeating Thomas Dewey in the 1948 presidential race. Olive Hill residents of the first few decades of the 20th century would claim the heart of the city to be the two Olive Hill brick plants. In 1942, the two plants employed 1,700 people, almost the whole population of Olive Hill today. They fired out a lot of bricks that made steel for our World War II effort. In the 1920s the plants sponsored the "Brickies," a traveling amateur baseball team. Olive Hill had a reputation for being a Saturday (and Saturday night) town. A few news clippings around the turn of the 20th century demonstrate that law enforcement was sparse, while vigilantism was a normal part of life. Some examples: » December 4, 1907 OLIVE HILL -- In a free-for-all fight at a distillery near Olive Hill, Frank Hall was shot and killed and Charlie Garvin was stabbed nine times and is not expected to live. » July 21, 1908 OLIVE HILL -- Elmer James, aged 19 years, living six miles north of here, was found dead in the road today. He left his wife and baby early in the morning to work his crop. Before noon a passing neighbor found him with a gunshot wound through the back. There is no clue. A pair of unfinished books In comparison to their earlier histories, Carter County, Olive Hill, Richland County and Mansfield have fallen on different times. Theirs is a crossroads story, geographically and spiritually. Carter County's natural resources were plentiful, but they were not unlimited. Eventually, as the fires suffocated the cold crept in. Carter Countians ran out of new raw materials to prosper from and the non-mined, job-related activities could not carry the county's economic burden. However, early release of the latest census shows Carter County and Olive Hill having a slight population growth, reversing a long standing trend. The region's proud history is an ongoing saga. Richland County has a rich history of leadership and resilience. History identifies Richland County and Mansfield as a railroad, agricultural and manufacturer leader. Mansfield, once referred to as "Little Chicago," has a boom town mentality, demonstrating it knows how to ride the tide. It may appear to some that Richland County and Mansfield are down and out when, in reality, the next chapter is just being penned. There are many Richland County residents today with descendants living and buried in Carter County. The four geographies will be linked for a long time yet. A deeper read about these four will find dedicated leaders, and community and faith-based groups working hard to enhance the quality of life in their respective communities. The spirit of the past is alive. Willie Davis is an Ontario High School graduate, a marketing consultant and Mansfield resident. He can be reached at willied@neo.rr.com.