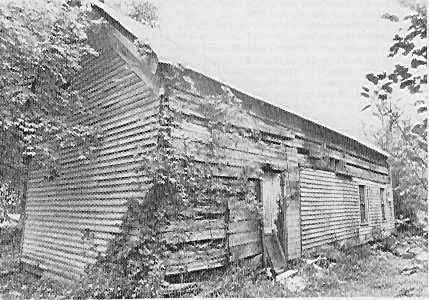

"Fort

Underwood" at Dry Branch, near Olive Hill, Ky., nearly 100 years

after the death of George Underwood.

"Fort

Underwood" at Dry Branch, near Olive Hill, Ky., nearly 100 years

after the death of George Underwood.

A version of the Hatfield-McCoy feud took place in the westernmost section of Carter County and extended over into Lewis and Rowan counties. Called the Underwood War, it pitted the Underwoods against the Holbrooks and Stampers, and though the latter group followed its vow to pluck out the Underwoods, root and branch, everyone at the time came out losers. There were many versions of the War printed in the local newspapers at the time. The Portsmouth Times of the day reported the following:

Writing from this distance, with only the colored stories of the friends of each clan to guide us, it is difficult to form a clear opinion as to which of the two warring families was to blame... Throughout all the years the Holbrooks and Underwoods have been committing murder the Holbrooks were as handy with the deadly weapons as the Underwoods...

In 1877, Boyd Countians read the following about the continuing feud:

Viewed in light of recent events, the neighboring county of Carter is highly suggestive to the uninitiated of general anarchy and confusion, a place where snakes stalk rampant and Underwoods and Stampers meet in deadly battle three times as day.

Pieced together here is a generally-accepted version of the War, following reports in contemporary newspapers, a compilation by Coates, and modern explorations by Ronald Burchett and Charles J. Pelfrey:

George Underwood,

Virginian by birth, came to the upper reaches of Tygarts Creek about 1847,

bringing with him his wife and four sons, Alfred, Jesse, Elvin, and George

Lewis. Old George, born in 1810, was six feet tall, rawboned, squareshouldered,

and inclined to be in fights at election time --a common practice.

He was a Whig, a Union man, and a Republican, and those political attachments

may have been more responsible for the friction than anything else.

The roots of the fight may have been planted before he arrived, for

John Stamper and George Penland were in a court suit as early

as 1845. But the ultimate sin of the Underwoods, or for which

they were blamed, was one which they learned and practiced with vigor during

the Civil War--the taking of horses. Alfred led a raid on Maysville

during the war, pillaging residences and stores of Southern sympathizers

while a provost guard (Union) looked the other way.

George had a strong reputation

himself and made the newspaper often. In 1872, Big Sandy Herald reported

him active at a meeting of Radicals (Republicans). Prior to that

time, apparently, he had been wounded in Olive Hill by one of the Tyree

boys. That family apparently held a tenuous relationship with the

Underwoods,

for Zachariah Tyree had early land suits with George but appeared

on the political stump with him after the shooting. In 1874, the

Herald said Alfred and Jesse, "two notorious outlaws who have probably

stolen more in Kentucky than any other ten thieves, have stolen horses

in Kansas and gone in the direction of the Indian Territory." These

hints at local reputation come from an opposition paper, give a look at

how the Underwoods were viewed by their contemporary foes five years

before the great battles.

George had a nephew by marriage,

John Richards Tabor, a card player. With help from his uncle,

he rented a small farm nearby in conjunction with John Martin.

In 1877 those two were accused of horse-taking. Soon afterward one

of the Stampers missed a horse he prized and blamed it on one of

the Pendlums, who was then killed from ambush. On his way

to the wake, George, too, was ambushed and shot eight times, but escaped.

He lost one eye and was crippled for life. Later that day, apparently,

the same shooters called George Lewis Underwood from his home and

shot him as he appeared unarmed in the doorway of his cabin. He would

lay abed for two years.

Claib Jones sided

with the Underwoods, saying he was called there by Dr. John Steele

to tend Lewis. "The Stamper party sent word they would burn my house

and kill my children; I sent back word if they had no houses they could

talk about burning mine... When our men went out and came back, our password

was 'another crow has fallen'. It went on and one morning seven crows

were killed before breakfast." (Author's note: the figure is

unsubstantiated.)

After that, old George healed,

Tabor

ran away, and Elvin joined the fight, with help from Martin.

Those two took to the bush with intent of vengeance and quickly two from

the other side were killed from ambush. Both had boasted of killing

a Pendlum. Elvin made no concealment of his involvement in

the latest assassinations. Matters became so raw Gov. McCreary

sent weapons, equipping J.N. Stewart and 40 local guardsmen and

telling them to keep order. The guns were kept in a room in the courthouse

at Grayson.

Now Jesse came back from

Iowa, where he had gone to avoid arrest over horsestealing charges in Kentucky

and Kansas. Before he left, he had been shot by one of the Holbrook

sons. With force, he arranged a sort of peace, then started back westward

by wagon. His family was overtaken in Lewis County, where the band

tried to kill him, but he got one of them, a man named Ruggles.

Jesse was wounded and returned to Grayson, charged with murder, but was

later acquitted because the make-shift posse had either incorrect authorization

or insufficient identification.

Martin withdrew from the

neighborhood and Elvin tried to go back to farming, but it was too late.

He was shot down in the presence of his two daughters (grand daughters

of David Davis and Allice Kilgore pictured above) who were

dropping seed corn ahead of his planting. There were sporadic minor shootings

for two months, and then on August 22, 1879, George Lewis Underwood

died of his two-year-old wounds. It was breaking the point in the

feud.

Within days Squire Holbrook

was shot down in his own yard and Jesse was credited, along with Claiborne

Jones,

with the shooting. Then all hell fell on the Underwoods.

William died of a gunblast through a window as he ate supper in his Rowan

County home. George turned his back when friends told him to get

out of Kentucky and on October 9, as he went outside his fortress home

to pick up firewood, his enemies waited until his arms were loaded and

then shot him near the door. Tough old George was helped inside by

the womenfolk, and word went out he was abed. A week later, Jesse

went to Fort Underwood to see about his father, but was cut down

as he passed through the dog-trot between house and kitchen. The

women kept pouring water on him to keep him alive, but he died that evening

(Oct. 16).

Two explicit newspaper accounts tell of this time of horror. The first comes from the Iron Register quoting the Greenup Independent:

George; Mrs. Parish,

his sister-in-law; Jane, his daughter; Elva's Mary (remember Mary and her

sister saw their father, Elvin murdered in the cornfield) and Mrs. Edna

Griffith were in the house. The women folks had been sitting up with

Jesse's corpse, waiting anxiously for help and protection from the county

authorities whom they had prayed for it.

Jesse's body was rotting

and filling with stench the home of his father, whose own body was commencing

to decay; the atmosphere inhaled by the children and wives was poisoned

by the fearful vapors arising from the beloved ones.

It was ten o'clock at night

Sunday evening when suddenly from 25 to 30 men with blackened faces surrounded

the house demanding admission in order to search for Claib Jones

and John Martin, and assuring George that neither he nor any of

the women folks should be hurt. The door was then opened. Fifteen

of them entered, two of them with cocked guns which they

kept ready for service while they stayed. George was sitting

on the side of this bed.

The talk was about the incidents

of the Underwood War and the men stayed nearly an hour. They uncovered

Jesse's corpse and making jokes about the unfortunate dead, they laughed

rudely and coarsely. Finally, after having secured all the arms in

the house one of the gang said, "Let us bring the meeting to a close."

Another then asked George to show him his latest wound, and when he stooped

over to show them his arm, one of the murderers emptied his gun, loaded

with slugs and shot, into George breast, piercing his body, the hole being

as large as a man's fist. Another of the assassins then shot him in the

back of the head, and 25 minutes later George was a corpse. The powder

of one of the shots burned Jane's dress.

Added is this chastisement printed as the end of the article in the Portsmouth times:

Be it ever said to the disgrace of Carter County that when the Judge ordered the sheriff to go with a posse of men to bury the dead, only two of many summoned would agree to go and the attempt was abandoned. Finally, one man in the Underwood neighborhood did go and bury the dead when the assassins had left the scene.

The above newspaper articles

were reprinted in George Wolfford's "Carter County, a Pictorial

History", published by WWW Company, Ashland, Kentucky.

For those interested in another side of the story, here is a letter to the editor, written by the infamous Jesse Underwood, and published in the 9 Oct 1879 (very close to the time of his murder) in "The Flemingsburg Democrat":

"I have been a silent listener to all that editors and local editors

have seen cause to write concerning the so-called Underwood War,

I consider that name unjust. It would be more appropriate to say

the war on the Underwoods, if it should be called a war at all.

I consider it downright murder, at least on their part, the other is quite

different. They commenced the shooting and

killing without a cause, and killed two men and seriously wounded another

and threatened the whole family before the Underwoods ever raised

a gun. They then had two men killed in arms. There was a peace

effected in which I

arrived in time to take a part. The Underwoods considered the

shooting at an end. Two years passed and Elvy Underwood was

murdered by two men while quietly at work in his field surrounded by his

little children. I trailed the two men direct within two hundred

yards of Squire V. Holbrook's house, as near as I dare go.

One of the tracks corresponded exactly with that of Squire Holbrook's.

Not content with what they had already done, Squire Holbrook, his

son Mildred and two others waylayed the road for me one whole day about

one-half mile from our house. Your readers have already learned their

leader's fate and how the followers murdered Wm. Underwood, unsuspected

and unawares, for he had ever labored for peace and never raised arms against

the enemies of his family. Next comes the shooting and wounding of

David Wilson, one of Holbrook's band. Your kind readers have

a right to censure whom they choose for this deplorable state of affairs

on Tygart. But one thing is certain, I have labored hard to prevent

this terrible work, for there is nothing I prize so high as peace and quiet.

(signed) Jesse Underwood"

Additional folklore says that the "Regulators" forced their way into

the house and, after making certain that Jesse was dead and after murdering

George, they ordered the womenfolk to cook them a meal, which they ate,

in full view of the bodies. Then they gave an ultimatum to the women,

saying that they had 24 hours to get out of the county. The women,

who must have been pretty brave, defied them and remained. Jane,

whose birth name was Melissa Jane was later changed to Rebecca Jane, when

she left Carter Co. to join other family members in Elkhart, Polk

Co., IA.

Submitted by Garrett and Sherry Lowe