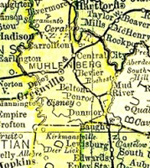

Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History

Airdrie

About the year 1853 R.A. Alexander, a native of Scotland, bought a tract of land near Paradise Muhlenberg County, Kentucky, known as the McLain survey, being the same land on which McLain opened a coal mine some years previous to selling to Alexander. McLain mined coal, loaded it on flat boats, and floated it to New Orleans. The coal was known as No. 11. Alexander brought some fifty or sixty families over from Scotland and established homes for them about one half-mile below or north of Paradise. They immediately went to work building dwellings, stores, barns and other necessary buildings for permanent homes. All the men were expert mechanics, engineers, stone masons, carpenters, businessmen and architects.

After their homes were made comfortable they turned to the work of preparing for elaborate iron works, patterned after the works owned by Alexander in Scotland. They built a dressed stone house for an engine room. It was two stories high, had a solid stone wall across the center, and was covered with slate. Every stone in the building was dressed by hand and hoisted to place by wind lasses turned by man power. They had an engine built in Scotland, as were the boilers, and shipped to New Orleans, then up the Mississippi, Ohio and Green rivers in barges, and discharged within a few hundred feet of the engine room. The engine was about seven feet long and twelve or fourteen inches in diameter. It was set on end in the north east corner of the room, the upper end being level with the floor. The boilers were two-flued, and there were eighteen of them, set in two batteries of nine each. They were placed near the south end of the engine room at the foot of a flight of stone steps running to the level of the tunnel through the hill. There vas a casting weighing tons balanced on the center wall of the engine room, one end of which was attached to the piston of the engine and the other to a fly-wheel that was twenty-five feet in diameter. Pump pistons for water and air were attached to this casting (called a walking-beam.) Between the engine room and the bluff there was a large water reservoir, that would hold thousands of gallons of water, also a large tank for storage of air, which was forced into it by the pump. The tank was about forty feet long and in the shape of a huge boiler. On this tank was a safety-valve that would open at a certain pressure, and the escaping air from this valve could be heard for miles. It annoyed the whole country for ten miles around and was very disagreeable, disturbing the rest of the people, especially the sick. From this tank the air passed through a furnace where it was heated to an extremely high temperature. A small hole was made in one of the pipes to test the hot air before it was forced into the smelting-furnace near by. The hole was not larger than a cambric needle. Open it and pass a bar of lead across it and the hot air would cut it into so quick that you could not see it.

The smelting-stack was built up level with the mine opening and the ore and coal were wheeled by hand from the yard and dumped into it. The coal was charred before it was used. The iron-ore was mined something like a half-mile west of the furnace and was trammed through the hill by mule power. After the ore was melted, the stack was tapped, the molten mass run out through a ditch or canal made of sand, into the moulding yard, where it was allowed to cool in the moulds. The yard was located between the stack and the river, in front of the stack. When the iron cooled they broke off the pig from the main lead, and stacked it up ready for shipping. The stone that was used for building the engine room and the stack was quarried from the ground where they now stand. A large mill was built south of the engine room; it was about 100 feet long and 50 feet wide. A saw mill, brick mill and other machinery were placed in it. All the brick mad there were what is known as fire brick. The kilns for burning the brick were located between the engine room and the mill. They sank a shaft about a half mill west of the hill, to a depth of 450 feet. I have heard it said that no one except the “bosses” knew for what it was sunk.

I lived about one mile due east from the works and was often there during its building and operation. When the furnace was in full blast one could sit in our yard on the darkest night and read a newspaper. Many a night I have studied my school lessons at our hoe by the light of the furnace. At that time the Green River country was almost a wilderness and had limited markets for such products as were raised. Tobacco and pork had to be marketed in New Orleans. Home consumption of garden stuff was the only market for vegetables. Airdrie was the first local market in the valley. I have delivered vegetables in Airdrie many times and it was always a cash business. We were paid in gold principally. The gold was in denominations of $20.00, $10.00, $5.00, $2.50 and $1.00, silver in 3c, 5c, 10c, 25c and 50c, and for dollars there was the five franc piece, a French coin worth 95c in gold. The Scots were a lively lot. They soon became familiar with the natives and were getting up amusements for the youngsters, especially dancing parties. I was about 14 years old and had never seen a dancing party. My people believed dancing was a cardinal sin, but like most youngsters I was ready for any new thing that came down the pike. So some of my pals and I would sneak out and go to the balls, and then slip back to bed in time to be called to breakfast in the morning. I learned to go through the old fashioned cotillion, the Virginia reel and a few jig steps, on old Airdrie Hill and I have never been able to get it out of my system since notwithstanding I am nearly eighty years young.

I have spent days and days wandering around and through Airdrie and you must know that I did not wander alone. There were always numerous youngsters ready for any kind of a frolic, and let me say, that there were many attractive girls in Airdrie. About the year 1857-8 the works shut down, or they found the metal was so hard that it could not be profitably worked. They then sent to St. Louis and barged what they called Black-Band Ore to mix with the Airdrie iron ore. They then started the works again and made one or two runs, but with little success. The war between the States came on, the works shut down, and the people scattered out through the two counties of Muhlenberg and Ohio. Today we have descendants of these hard-headed Scotchmen all around us and I am glad to say that they are rated as A. 1 Citizens, good neighbors, honest as the day is long, first class patriots, ready to defend our flag against all [newspaper damaged] of this class of Scots in our country. After the War closed Gen. Don Carlos Buell became the owner of the land immediately in and around Airdrie. He and Dr. S.A. Jackson operated the coal mines for a time using barges to deliver, with tow boats to propel the barges instead of floating them, as did the McClains. In the year 1866 the legislature ceded the navigation rights to a company for 20 years. They soon began to tax all river craft carrying products on Green River. The tariff was so high on coal that there was no profit in producing it on Green River and the Airdrie works shut down again and have not been revived to this day.

Airdrie is now a resort for picnicking and fishing. All the machinery houses and material have been scrapped and sold, nothing remaining except the engine room and the stack. The slate off the roof whas long since been carried away by piecemeal. Large trees have grown up in the moulding yards, in the reservoir and the brick kilns. The roads and yards are fast becoming thickets of briers and small timber, blackberries growing where it was hotter than the underworld is said to be. Several years ago, the State determined to build a branch prison at Eddyville, Ky. They contracted for the stone at Airdrie, sent a lot of prisoners from Frankfort to load the stone on barges and bring it to Rockport and transfer it to cars to ship to Eddyville but, before they had shipped any stone they found that they could work the stone at less cost nearer the new prison. While the convicts were at Airdrie they were housed in the old engine room. Some years ago some writer to the Cincinnati and Louisville papers, through ignorance or willful misrepresentation, wrote Airdrie up as a penal institution. This was all out of line; it was never intended, or used for a prison, except as stated above. Referring again to the people of Airdrie, I do not want to leave the impression that the good Scots were immoral. They were as a class strictly moral, and held to the Presbyterian faith with all the tenacity of their old forebear. The Pattersons Duncans, Heaths, Tolls, McDougals, Sneddons, Wilsons, Keiths, Williamsons, Hamiltons, Kelleys, Terrences and many other families are among the best citizens Ohio and Muhlenberg counties have. They are capable, energetic, honorable and true men and women, leaders in church and school a little clannish in that they almost unanimously hold the Presbyterian faith, and generally practice what they preach. They make good soldiers, good mechanics, good farmers, good preachers and above all good neighbors. I am one among a few men who were intimate with Old Airdrie from its first stroke on the hills of Muhlenberg County to the present date. It virtually was, and is my native home. Many memories of my boyhood and later manhood are centered in and around Old Airdrie.

Source: Reid, Lycurgus T. “Airdrie.” Hartford Herald [KY], 13 July 1921.

Updated August 22, 2024.