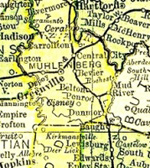

Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History

Airdrie

Alexander Stewart Cather was born of Scottish ancestry January 6, 1917, in Bruceville, Indiana. He obtained his B.A. degree from Western Kentucky College (Western Kentucky University) in 1941. He served in the army in France, England, and Germany during World War II, and visited relatives in Scotland. One of his cousins lived near Busby, close to where Rudolph Hess parachuted. An uncle lived at Strathaven not far from Glasgow. After returning to the United States, he taught history at Central City from 1945 to 1981. With a lifelong interest in Airdrie, Cather is the source for the following description of the iron furnace.

Airdrie and its iron furnace on the Green River were built in 1855 by Robert Sproul Crawford Aitchison Alexander of Scotland who believed the Scots were the most competent iron workers in the world. He brought many of his former employees and their families to New Airdrie, Kentucky. Evidently they didn't realize that the ore in Kentucky required a different treatment for after three or four unsuccessful attempts to run iron, the furnace was discontinued.

The hill above the furnace was the location of the town which consisted of 25 or more houses, a hotel, and the store. No trace of the buildings that were built on Airdrie Hill can now be found. Some of the houses were carried off for lumber; others tumbled down and rotted. The Don Carlos Buell residence, erected by William McLean before Airdrie was started, was not only the largest and oldest residence but was also one of the last to be destroyed. Standing in the beautiful park near the top of Airdrie Hill, this house burned down in 1907. The landscape viewed from this spot up and down the Green River overlooks the forest and farms of Ohio County. The winding paths to the furnace are covered with honeysuckle, ivy, and other undergrowth. The footbridges have disappeared.

On the narrow strip of land between the river's edge and the hill running parallel with the river is now found the only evidence of the old iron works. Among the cedars and the sycamores are the ruins of the large brick chimney. Here and there protruding from the ground can be seen the old stone walls, the fortress-like old prison or machinery house. This hand-hewed stone building with fortificiation-like walls resembles and old deteriorating medieval castle. The smokestack of the furnace still stands 55 feet or more in height, and the stone house near it has massive walls that seem able to defy storm and sunshine for many years to come. This sandstone structure, 50 by 20 feet with three stories, lost its wooden beams, floors, and window frames long ago. There is a long flight of stone steps leading up to the upper level where it is about level with the structure. In the large building there is a shaft not more than 10 feet deep that is partially filled with trash; the walls of this structure are over three feet thick with holes hallowed out for heavy wooden beams that once supported the second and third floors.

Born in 1896 at McHenry, Kentucky, Agnes Simpson Harralson moved to Greenville when she was fifteen years old. She began teaching in 1914 in North Carolina and returned in 1918 to Muhlenberg County. She then worked in the company store of the Duncan Coal Company at Graham; later she obatined the postmastership. There she met John H. Harralson, a young doctor. This was during World War I, and Dr. Harralson was one of the 100 doctors the United States government “loaned” to the British because of the depletion of their doctors in the war. He stayed an additional six months in England to study in their facilities and returned in 1921. In 1925 Agnes married John Harralson, and in 1930 they moved to Central city.

Upon the death of Dr. Harralson in 1951, she worked for the Central City Times Argus as social editor.

During her lifetime she wrote to soldiers in the wars. If any Muhlenberg County soldier wanted a letter from home, she would write him. Both World War I and World War II soldiers received letters; the number of letters in the first world war was smaller than the unbelievably large list of those in the second world war that exceeded 500. She wrote these letters in longhand, duplicated them, and mailed them to the soldiers. Her “godsons” called on her during their furloughs, and the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars honor her in parades and have affectionately named her “Mrs. H.”.

Author of Steamboats of the Green and the Colorful Men Who Operated Them (Berea, Ky., 1981), Mrs. Harralson readily shares her knowledge of the history, stories, and legends of Muhlenberg County. The following edited stories are based on an interview with her on November 12, 1981.

The legend of Paradise is that anything that has ever happened there has been a failure. Airdrie is about a short mile downstream from Paradise. Lord Alexander, a bachelor, who owned the Airdrie Iron Foundry in Scotland, had a brother in Kentucky who had settled in Woodford County and was interested in farming and raising thoroughbreds and fine cattle; he owned several thousands of acres of Bluegrass countryside. When Robert, Lord Alexander's oldest nephew, finished school in Kentucky, his uncled offered to further his education at Edinburgh and to let him inherit the title and iron works. After Robert completed his schooling at Edinburgh, he went to Airdrie; he liked the work and the people and was a success. Called young Lord Alexander, he inherited the title when his uncle died. However, as the years went on, the ore in Scotland became scarce, and it was obvious that there was only a limited number of years left for smelting iron.

At that time in the 1850's there were several little blast furnaces in Kentucky. Alexander got two geologists to come to Kentucky to investigate the success of the smelting industry; they reported that they believed the main problem of the furnaces in Kentucky was transportation to get the heavy product to market. Lord Alexander believed that if he built a modern furnace close to a coal mine and on a waterway that he could not fail. He came to Kentucky, bought 2,500 acres of land from the unsuccessful Buckner Furnace, and bought everything along the Green River until he eventually had 17,000 acres of ore land. He offered his employees in Scotland the chance to go with him to kentucky and he would underwrite their transportation and give them a living wage until the furnace was in operation. He brought stone cutters, carpenters, shaft men, pattern workers, and the regular iron workers. Many wanted to come such as the Duncans, the shaft men, and the McDouglas, and others.

This was the main topic of conversation in Airdrie, Scotland. There was apprehension too as crossing the ocean on sailing vessels was dangerous. Of the Duncan family, Mrs. Agnes S. Harralson's great-grandfather and his two older sons decided to come first and if it worked out for one year, they would send for the rest of the family. They were nearly two months crossing the Atlantic and were shipwrecked off the coast of Nova Scotia but close enough to shore that they were rescued. They were a “fur piece” from Kentucky, but they finally made their way to Pennsylvania without anything but what they had on their backs; they had taken passage on different ships and worked to pay their way. (Lord Alexander was not with them when they shipwrecked.) When they reached Pennsylvania, they worked in anthracite coal until the shaft was ready to be sunk at Airdrie.

The rest of the Scots had come down the Ohio River and up the Green River to Paradise. There were not enough houses in Paradise to take care of hardly any of them so they just had to do the best they could. The first thing they did was to build homes and a three-story hotel. And, then they made this huge thing, the furnace, and everything looked like it was just going to be wonderful. For two years they built and everyone had high hopes that this was going to be the biggest thing in Kentucky.

As the Scots had always fired their furnances with raw coal, they didn't see any reason why they shouldn't in Kentucky. It worked in Scotland, and as the coal mine was right next to the furnace, they could take wheelbarrows and dump coal into the furnace. The Kentuckians kept saying, “But, in Kentucky we use charcoal; coal won't make a hot-enough fire.” Mrs. Harralson comments, “I'm a Scotsman, and I'll tell you this: you can always tell a Scotsman, but you can't tell him much; he already knows it.” The Scots just wouldn't listen to the Kentuckians and try charcoal.

The first run was a gala affair as everyone had come from miles around to see the first run of metal. They made a few bars of pig iron and that was it. They tried again and that went on until Alexander got sick of it; he had invested about $360,000, a fortune. Finally, he told them they could try one more time, and if it was a failure, he was through.

The next time was just the same, and, true to his word, Lord Alexander left them stranded without any money or means of making a living.

The workers were of a different culture and had some difficulty starting life anew. The Scots liked the Kentuckians, but the Kentuckians didn't trust them completely; because of the Scottish brogue it was difficult to understand them, and they wouldn't take the suggestions to try charcoal. The Duncans opened a coal mine at Aberdeen and provided employment; the McDougals began mining and shipping coal; and the Hadens employed several of the Scots at their sawmill. By this time they had become naturalized citizens.

In Mrs. Harralson's words, the failure of the furnace and the abandonment by Lord Alexander “was just such a disappointment! One had to be in the family and to hear it all your life to know how hurt they were.”

Recent Research from Scotland

Airdrie on the Green River in Muhlenberg County is “New” Airdrie for “Old” Airdrie is in the County of Lanark, Scotland. A reasonable question to ask is what memories or records exist in Scotland about the “experiement” in America. The following research evidences a desire in Scotland to erase the unpleasant recollections of Airdrie, Kentucky, and a less than favorable opinion of the Alexander family.

A native of Evansville, Indiana, Larry W. Griffin graduated from the University of Evansville, the University of Kentucky, and obtained a Masters Degree in Library Science from Indiana University. He has taught at Murray State University,, Murray, Kentucky, Oakland City College, Oakland City, Indiana, and worked for several years as assistant librarian at the University of Evansville. Then after moving to Bloomington, Indiana, to work in the Indiana University Libraries, he became an Exchange Librarian with the Edinburgh University Libraries, Scotland, in 1980-1981. Aware of the Airdrie, Kentucky, story, he resolved while at Edinburgh to research the Scottish account of the experiment. The following document is the product of his research. Source: Larry W. Griffin, Exchange Librarian (on leave from Indiana University Libraries), Edinburgh University Libraries, Scotland.

New Airdrie and Old Airdrie

As an American in Scotland, I was quite interested in the “New Airdrie” experiment and was keen on pursuing both Alexander S. Cather's and Agnes S. Harralson's accounts of the venture on this side of the Atlantic. When stories of events of the past are passed down through families by word-of-mouth, facts, events, and interpretations of them become altered, and after searching for accounts of the venture in the Edinburgh University Library, the Naitonal Library of Scotland, and the Airdrie Public Library(1), three points of interest emerged:

- sources in Scotland do not mention the New Airdrie experiment;

- some of the facts do not coincide with legendary accounts; and

- sources in Scotland indicate a less than favorable attitude toward the Alexanders of Kentucky.

Airdire, Scotland, is a “large industrial burgh” in the County of Lanark, located about eleven miles east of Glasgow and has a population of 37,908.(2) In 1831 the population was 6,594.(3) The exact origin of the name is disputed, but the most popular explanation is that Airdrie means “King's Hill,” an allusion to the Battle of Aerderyth.(4) The Alexanders of Airdrie date back to the fifteenth century and are a branch of the Alexanders of Stirling.(5)

In the search for records of the New Airdrie experiment, the most perplexing fact was the lack of recorded evidence of it. Since the experiment was not successful, it is likely that the Alexander family did not publicize or discuss the venture formally. Could it have been regarded as a misadventure of the youthful “young Robert”, an adventure the family preferred to forget? Mrs. Harralson's recollections of young Robert's attitude toward the stranded Scots lends credence to such a possibility. Correspondence between Robert Sproul Crawford Aitchison Alexander and Henry Charles Deedes, Commissioner of the Airdrie House Estates in Scotland (and brother-in-law of the former), may mention this venture, but to date no such correspondence has been located. If the New Airdrie experiment was “the main topic of conversation in Airdrie, Scotland,” as Mrs. Harralson recalls, it does not appear in any formal accounts. Such a topic, of course, would be of most interest to working-class persons who do not normally keep journals and diaries; nor would their conversations about possible emigration to America tend to reach the pages of newspapers.

No documentation thus far has been found that mentions that New Airdrie employees were brought directly from an iron works in Airdrie, Scotland, for the purpose of working in Kentucky. Why would a Scotsman want to emigrate at a time when the iron trade was still active? The great depression in the iron trade did not occur until 1858-1863(6). Is it possible that the “former employees” and their families that were brought to New Airdrie did not come directly from Scotland for the express purpose of working in New Airdire, Kentucky, but went initially to Nova Scotia, and unable to make a living there, were “recruited” into the New Airdrie experiment? Mrs. Harralson's recollections allow this possibility. Also, a shipping trade between the Alexander family in Airdrie [Scotland] and Nova Scotia dates back as far as 1630.(7) Moreover, a photograph of a letterhead for the Airdrie Iron Foundry indicates that as of 1870 the foundry was owned by the Trustees of the late Jane Smith(8). The other owners of the Airdrie foundry were Sir William Alexander, brother of Robert Alexander of Woodburn, Kentucky, and uncle of R.S.C.A. Alexander. No other owner has been traced so far.

In 1814 Robert Alexander, the original owner of the Woodburn Estate, near Versailles, Kentucky, married Eliza, daughter of Daniel Weisiger of Frankfort. They had three sons and two daughters. One of the daughters, Mary Bell, married Henry Charles Deedes, Commissioner of the Airdrie Estate in Scotland. William Alexander, the eldest son, was born in 1816 and died in 1817. Robert, the second son, was born October 25, 1819, and was educated at Cambridge(9). He succeeded to the Airdrie Estate when his uncle, Sir William Alexander, Lord Chief Baron of the Court of Exchequer at Westminster, died in 1842. At that time he added to his patronymic the names Sproul Crawford Aitchison. Robert died unmarried on December 1, 1867(10). Upon his death, the third son, Alexander John Alexander, succeeded to the estates of Woodburn and Airdrie and is the Alexander associated with the Woodburn stud farm in later accounts(11).

No evidence has been found, thus far, linking R.S.C.A. Alexander with an iron foundry in either Airdrie or Kentucky. He is remembered in Scotland solely for his interest in breeding cattle and race horses(12). The people of Airdrie [Scotland] have long regarded the Alexanders as absentee landlords who lacked any concern for the community:

“It was no doubt unfortunate that when Airdrie first began to disclose her hidden treasures of coal and iron, the unexpected wealth which thereby accrued to the proprietors of Airdrie Estate all went to enrich individuals who were strangers and whose main interests were centred in England, but principally at Woodburn, Kentucky, U.S.A. The highly respected Mr. Deedes arrived on the scene too late, but even then he came only as Commissioner for the superior who lived in America. Indeed, it may be truly said that from the time of Robert Hamilton to that of the late Sir John Wilson, with perhaps the exception of the comparatively short period during which the kind-hearted Misses Aitchison reigned at Airdrie House, there was little or no interest evinced in the well-being of the community by any of the successive Lords of the Manor. What Airdrie really needed, the first half of last century, was a return of the good King Malcolm IV to repeat his drastic action towards Gilpatrick McKerren in 1160, by again dealing summarily with absentee-landowner-ship. Then perhaps there would have been some chance that the vast unearned wealth then being torn from beneath the town would not all have gone to beautify some ‘old Kentucky home far away’(13).”

Mrs. Harralson's account of R.S.C.A. Alexander's attitude toward the stranded workers confirms the above opinion of a Scotsman that the Alexanders were not gifted with “noblesse oblige”.

In conclusion, there are more questions raised than facts verified or answers given. While there are many possible sources yet to be sought out, the initial process of trying to sort out the facts presented in stories and legends often leads to few answers and many new questions, but such is the nature of research. As a practicing librarian, my time for research during the past year in Scotland has been limited; hopefully, in the future I shall be able to pursue the legend of “New Airdrie” and ultimately piece together a more complete account: the story of hard-working, independent, and courageous Americans with roots in Airdrie, Scotland.

LWG

1 April 1982

Edinburgh

Scotland

Notes

- Carol E. Smith, Local History Librarian, did considerable research at the Airdrie Public Library.

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica: Micropaedia (Chicago, 1974), vol. 1, p. 163.

- The New Statistical Account of Scotland: Lanark, Vol. IV (Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1845), p. 244.

- Williamson, A.G., Twixt Forth and Clyde (London: Nattali & Maurice Ltd., 1944, 1942), p. 38.

- “House of Alexander and Airdrie Estate: I,” Airdrie Advertiser and Linlithgowshire Standard, 7 Nov 1896, p. 4.

- The Book of Airdrie; being a Composite Picture of the Life of a Scottish Burgh by Its Inhabitants (Glasgow: Jackson, Son & Co., 1954), p. 28.

- Rogers, Charles, Memorials of the Earl of Stirling and the House of Alexander, vol. 1, p. 128.

- Photograph is located in the Local History Collection, Airdrie Public Library, 72 Wellwynd, Airdrie, Scotland.

- Alumni Cantabrigienses (Part II, vol. 1, p. 30) lists him as entering Trinity College at Cambridge in 1840 and receiving the B.A. in 1846. Other sources say he attended Oxford (Rogers).

- Rogers, vol. 2, p. 36 - 37.

- Rhodemyre, Susan, “Woodburn Stud,” The Thoroughbred Record 213 (1), 7 Jan 1981, p. 32 - 44.

- “House of Alexander and Airdrie Estate: II,” Airdrie Advertiser and Linlithgowshire Standard, 14 Nov 1896, p. 5.

- Knox, Sir James, Airdrie: A Historical Sketch (Airdrie, Scotland: Baird & Hamilton, 1921), p. 137.

Additional Reading

American historians offer a more thorough analysis of the New Airdrie experiment in Kentucky than historians in Scotland. Otto A. Rothert, >A History of Muhlenberg County (Louisville, 1913) presents a favorable view of the Alexander family as does Agnes S. Harralson, Steamboats on the Green and the Colorful Men Who Operated Them (Berea, Ky., 1981). However, Harralson does emphasize the way Lord Alexander abandoned the Scots at Airdrie which “stands nestled in the undergrowth on the bank of Green River like an old fortress, a symbol of failure and frustration”.

Larry W. Griffin offers new perspectives on the Airdrie story based on available sources in Scotland. A summary of the Scottish viewpoint which Griffin extracts from Sir James Knox, Airdrie: A Historical Sketch (Airdrie, Scotland, 1921) differs from that of the Kentuckians and is a harsh condemnation of the Alexander family. For additional sources see the notes following Griffin's account.

Source: Gooch, J.T. The Pennyrile: history, stories, legends. Madisonville, KY: Madisonville Community College, 1982. 64 - 67, 69 - 72.

Presented with the kind permission of J.T. Gooch

Updated July 12, 2022