Local History

Andrew Jackson Got One Vote in Muhlenberg County in President's Race

Lone vote cast by John F. Coffman, Jackson's bodyguard

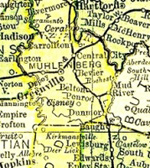

Colonel (later General and President) Andrew Jackson may have been a folk hero to his fellow Tennesseans, and he may have been able to fool the rest of the fledgling nation as to his acts of heroism at the Battle of New Orleans, but he didn't, for one minute, fool the voters of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky, in the presendential election of 1824.

So fierce was the animosity toward the man known as “Old Hickory” that he received only one vote in Muhlenberg County in that election. The lone vote, according to recorded history, was cast by John F. Coffman who had served as special bodyguard for Colonel Jackson during the War of 1812.

As the story is related, Colonel Jackson and his American troops were standing in defense of the city of New Orleans and the free flow of traffic along the Mississippi River. On the opposite side of the battlefield was the British Redcoat Army, still smarting from their defeat at the hands of Continental Soldiers in the Revolutionary War, and still standing in hopes of defeating America and reverting this newly created nation to British dominance and colonialism.

In Muhlenberg county, young Capt. Alney McLean was busy raising a volunteer company to march to the aid of Colonel Jackson and his troops at New Orleans.

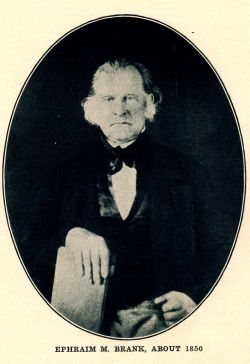

McLean's company arrived at the battle site just before hostilities began, just in time to take up positions on the breastworks facing the oncoming Redcoat Army. Included in the volunteers from Kentucky were a noted woodsman, Ephraim Brank, Greenville; Robert Craig, Greenville; and Mike Severs, who lived in the Pond Creek area of the county now known as Bevier.

Brank took his post atop the breastworks in a position later described in glorious detail by one of the advancing Redcoat officers, who was widely quoted in the newspapers of the day. The same was later printed in Robert McNutt McElroy's Kentucky in the Nation's History and in Otto A. Rothert's History of Muhlenberg County. The British officer described this battle in these glowing terms.

The British Officer's Story

“We marched in a solid column in a direct line upon the American defenses. I belonged to the staff, and as we advanced we watched through our glasses the position of the enemy , with that intensity an officer only feels when marching into the jaws of death. It was a strange sight, that breastwork, with a crowd of beings behind, their heads only visible above the line of defense. We could see distinctly their long rifles lying on the works, and the batteries in our front, with their giant mouths gaping toward us. We could also see the position of General Jackson, with his staff around him. What attracted our attention most was the figure of a tall man standing on the breastworks, dressed in linsey-woolsey, with buckskin leggings, and a broad-brimmed felt hat that fell round the face, almost concealing the features. He was standing in one of those picturesque, graceful attitudes peculiar to those natural men dwelling in the forests. The body rested on the left leg and swayed with a curved line upward. The right arm was extended, the hand grasping the rifle near the muzzle, the butt of which rested the toe of his right foot. With the left hand, he raised the brim of the hat from his eyes and seemed gazing intently on our advancing column. The cannon of the enemy had opened on us, and tore through our works with dreadful slaughter, but we continued to advance unwavering and cool as if nothing threatened our progress.

Motionless as a Statue

“The roar of the cannon had no effect upon the figure before us. He seemed fixed and motionless as a statue. At last he moved, threw back his hat brim over the crown with his left hand, raised the rifle to the shoulder, and took aim at our group.

“Our eyes were riveted upon him; at whom had he leveled his piece? The distance was so great that we looked at each other and smiled. We saw the rifle flash and very rightly conjectured that his aim was in the direction of our party. My right hand companion, as noble a fellow as ever rode at the head of a regiment, fell from his saddle.

“The hunter paused a few moments without moving his gun from his shoulder. Then he reloaded and assumed his former attitude. Throwing the hat brim over his eyes and again holding it up with the left hand, he fixed his gaze upon us as if hunting out another victim. Once more the hat brim was thrown back, and the gun raised to the shoulder. This time we did not smile, but cast glances at each other to see which of us must die.

“When again the rifle flased, another one of our party dropped to the earth. There was something most awful in this marching into certain death. The cannon and thousands of musket balls playing on our ranks we cared not for, there was a chance of escaping them. Most of us had walked as coolly upon batteries more destructive without quailing, but to know that every time that rifle was leveled toward us and the bullet sprang from the barrel, one of us must surely fall; to see it rest motionless as if poised on a rack, and to know, when the hammer came down, that the messenger of death drove unerringly to its goal; to know this, and still march on was awful. I could see nothing but the tall figure standing on the breastworks. He seemed phantom-like, higher and higher, assuming through the smoke, the supernatural appearance of some great spirit of death. Again did he reload and discharge his rifle with the same unfailing aim and the same unfailing results. It was with indescribable pleasure that I beheld, as we neared the American lines, the sulphurous cloud gathering around us and shutting that spectral hunter from our gaze.

“We lost the battle, and to my mind, the Kentucky rifleman contributed more to our defeat than anything else, for while he remained in our sight, our attention was drawn from our duties, and when at last he became enshrouded in the smoke, the work was complete. We were in utter confusion and unable, in the extremity, to restore sufficient order to make any successful attack. The battle was lost.”

Brank Identified as Rifleman

The man on the breastworks was identified by McElroy as Ephraim Brank of Greenville. The only discrepancy in this story, from the one which was later reprinted many times, is the fact that Brank did not reload his own rifle each time. He, it was written, fired these rifles as fast as Robert Craig and Mike Severs would reload them and pass the rifles back up to Brank.

The Battle of New Orleans was won by the American Army on January 8, 1815, thanks greatly to the heroics of the few but brave frontier soldiers from Kentucky. After this battle, Jackson rode his new-found, but possibly regained glory to generalship, and later, after one unsuccessful try, he became a two-term President.

For their part in the Battle of New Orleans, Brank, McLean, and others of the Muhlenberg contingent were given arduous and demeaning disciplinary duty by Jackson, Rothert later reported. This was possibly a balm for Jackson for being upstaged by the heroics of Brank and others. This punishment, following their heroics at New Orleans, was never forgotten nor forgiven by McLean or his men.

Back home in Greenville, Brank lived a simple life in a two-story dwelling on North Main Street in Greenville. The home stood until recent years when it was torn down and replaced by a more modern dwelling.

McLean entered politics in Muhlenberg County and soon became a district judge and a state legislator. He also later served as a U.S. Congressman from Kentucky.

McLean gained his long-awaited revenge on Jackson in the election of 1824. McLean flexed his local political muscle enough to sway Muhlenberg County voters to cast their votes, almost unanimously, for Jackson's bitter opponent, Henry Clay. Jackson, it must be noted here, won both the nation's popular and electoral vote in that election, but lost the Presidency to John Quincy Adams on the floor of the Federal House of Representatives. Jackson, however, was later elected to two terms as President, in 1824 and 1832.

Apparently the single vote cast by John F. Coffman for Jackson did not hurt his political standings in Muhlenberg County. Coffman was elected in 1827 and again in 1833 to serve as his county's legislator in the Kentucky House of Representatives.

Source: Anderson, Bobby. “Andrew Jackson Got One Vote in Muhlenberg County in President's Race.” Kentucky Explorer, 23(5), Oct 2008, pp. 40-41.

Updated July 14, 2022