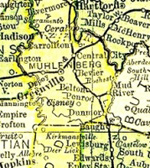

Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History: D

Mark Duvall's Discovery of “Silver Ore”

During the spring of 1851 an excitement was started in the western part of Muhlenberg County which continued for more than two years. Mark Duvall claimed he had found silver ore in the hills of his neighborhood. Mark Duvall was a son of Benjamin Duvall, an old settler who lived about six miles west of Greenville. Benjamin Duvall was the father of Howard, Mark, and Benjamin Duvall, Jr., or “Darky,” as he was commonly called.

Mark Duvall when a young man learned the tanner's trade under John Campbell of Greenville, who conducted a tannery near where the Greenville Milling Company's planing mill is now located. Mark had also devoted some time to the study of chemistry and mineralogy, and had become a good tanner. After remaining with Campbell for a few years he married and located near his father's farm, on which was a good running spring. There Mark established a tanyard of his own, which was well patronized. Mark was a quiet, sober, and well-liked man, and had the full confidence of all who knew him. In fact, the Duvall family stood high in the community.

There were about four hundred acres of hilly land lying east of Jarrell's Creek, all of which was owned by Benjamin Duvall and his neighbors. In the spring of 1851 Mark Duvall reported that he had discovered the existence of silver ore in this hilly section. He would not point out any particular spot where silver could be found, but declared that rich veins of it occurred throughout these hills. The proclamation of this news was very encouraging to those who owned the hills.

Steps were at once taken and prospecting commenced, and soon the digging of holes and pits was carried on in earnest. As the news of the great silver discovery spread, prospecting extended until everybody in the western part of the county was on the lookout for ore, and in a short time the whole county was more or less interested.

This was only a few years after the excitement of the Buckner and Churchill Iron Works had subsided. Some people seemed to take a great interest in the matter, while others scouted the idea. Secret investigations were conducted in different parts of the county, but the investigations made among the hills were boldly carried on with greater assurance. Several of the moneyed men of Greenville became interested in the silver project, and made arrangements to become partners with those owning the hills and to furnish means for a thorough investigation of the matter.

When Mark Duvall had declared that there was silver in the hills, he backed up his statement by melting “silver” out of the rock that had been mined by the landowners. Different kinds of rock had been dug up; some limestone, some iron ore, and a blue sandstone which sparkled with particles of mica, and was considered the richest and most plentiful of the “silver” ore.

Duvall had a novel way of extracting silver from this blue sandstone. He used a deep iron bowl with a long handle attached. It was simply a large ladle. Nearly every family owned a similar small ladle, which they used in those days for melting lead to make bullets for hunting purposes.

During the first year of the silver excitement Duvall would have the different parties who were digging beat up some of their ore, and he would take his big ladle, go to their houses, and make a “run” for them. These “runs” were usually made at night. After a hot wood fire was started Duvall would fill his big ladle with the powdered ore and place it on the fire. He would then put a flux of soap and borax in the ladle to “increase the heat” and “help extract the metal.” As a general thing there would be a gathering of neighbors to witness the “run.” After the ore had become red-hot, Duvall would add some “nitric and sulphuric acid,” which would soon disappear, and Duvall would say, “She has done her do!” He would next carry the ladle out doors, to cool off, and after it had cooled sufficiently a search would be made for silver. Small shots of metal would be found and selected out of the ore that had been heated, and much rejoicing would take place.

The next day digging would be resumed with more earnestness. After a while the natives tried to extract the silver from the ore themselves.

The line that, before the formation of Muhlenberg, separated Logan from Christian and lay within the bounds of what became Muhlenberg, is described in the act creating Christian County as follows: “Beginning on Green river, eight miles below the mouth of Muddy river [Footnote]; thence a straight line to one mile west of Benjamin Hardin's.” In other words, this former dividing line ran in a southwesterly direction from a point on Green River eight miles below the mouth of Mud River to a point in the neighborhood of what later became the northwest corner of Todd County. That being the fact, about three fourths of the original area of Muhlenberg County, or about two thirds of the present area, was taken from Christian, and the remainder - the southeastern part of Muhlenberg - was taken from Logan County.

I judge that after the southern line had been surveyed it was discovered that certain lands originally intended to fall within the bounds of Muhlenberg were, according to the “calls for running the county line,” not included in the new county. At any rate, on December 4, 1800, the Legislature passed “An act to amend and explain an act, entitled ‘an act for the division of Christian county,’” which I here quote in full: take a forked stick or small rod, like those used by “water witches,” and “locate” veins of silver as easily as a “water witch” could locate a vein of water.

I recall a man named Culbertson, who wore trousers that did not reach his shoetops, and were therefore called “highwater pants.” He carried a small, greasy bag, filled with various kinds of ores. He used a short hickory stick, split at one end. In order to find a vein of any particular metal he would place a piece of that kind of ore in the split end of the stick. With this loaded “metal-rod” he would walk over the hills and shake it around at arm's length and in every direction. If the ore that existed in the ground was the same as the ore in his split rod, then, he claimed, the attraction became so great that it jerked his arm like a fish.

John Vickers, who lived between Sacramento and Rumsey, was one of the great water and metal “witches” of his day. He was elected to the Legislature in 1848, went to California in 1849 when the gold fever broke out there, but returned to Muhlenberg in the fall of 1851 in time to assist Duvall in trying to convince the people that silver existed in the region of Jarrell's Creek. He claimed that he had found many silver veins with the assistance of his rod. He told the people that one day, while sitting in his house in Sacramento, he located, with his hickory rod, a rich gold vein in California, and that he had written to some of his relatives in that state to take possession of it until he could get there. He said that an abundance of silver undoubtedly existed in the Muhlenberg hills. His statements added luster and vigor to the project.

The various “water witches” became expert “silver witches,” and “located” many rich veins throughout the neighborhood. There were several old women who followed telling fortunes with coffee-grounds. They also tried their skill on the silver question by “turning the cup,” as they called it. They put some coffee-grounds into a cup with a little coffee and turned the cup around very rapidly, shook it, and then turned the cup upside down in the saucer. They would let the inverted cup remain in that position a few minutes, and then pick it up and examine the position of the grounds that still adhered to the sides. From the arrangement of the grounds they could tell whether the prospects were “clear” or “cloudy.” If there was a clear space down the side of the cup it indicated “good luck” and “go ahead.” If the side of the cup was clouded with grounds it foretold “bad luck” and “look out.”

The rod was considered the most reliable way of determining the presence of silver ore. The “silver witch” in using the rod could answer questions with a “yes” or “no.” The nodding up and down of the rod was for “yes” and the horizontal movement for “no.” There was great confidence placed in these indications made by the rod.

As a general thing the people in the county had but little knowledge of mineralogy, metallurgy, or chemistry. Doctor W.H. Yost was considered the most competent man in Muhlenberg to make a test of the metal. After an examination he pronounced it tin. Howard Duvall, a brother of Mark, melted a silver dime and took it to Doctor Yost for analysis, who declared that it also was tin. The result was that the prospectors lost faith in Doctor Yost's knowledge of metals.

After Doctor Yost had made his tests it was thought best by the leaders of the silver enthusiasts to have the ore and metal analyzed by experienced chemists and mineralogists, for no one except Mark Duvall had succeeded in getting any metal from the blue sandstone which had been dug out of Silver Hills. A meeting was held by parties interested in the project.

George W. Short, of Greenville, together with Duvall, was delegated to take some of the ore and metal that Duvall claimed to have extracted by the use of his iron ladle and a wood fire, and go to Cincinnati to an experienced assayer and have both rock and metal tested. This they did. The chemist stated that the so-called “silver” was a mixture of metals, and declared that it could not possibly have come out of the sand rock, for the rock contained no metal of any kind. Duvall argued that it did. So Short and Duvall left Cincinnati without any encouragement. Soon after this, Short lost all confidence in the silver business and withdrew his support and influence.

In spite of this set-back, much interest was still manifested by many of the owners of the so-called Silver Hills. Dabney A. Martin, a merchant and tobacconist of Greenville, wanted another test made.

So when he went to Philadelphia after goods he took with him some of the blue sandstone and the metal that Duvall claimed to have “run” from the rock, and had them tested by chemists there. They also told him that the “silver” was a mixture of metals, and that it had not come out of the rock. In the fall of 1852, when Dabney A. Martin went to Europe on tobacco business, he took some of the ore and metal to England and had them analyzed in London. The chemists there likewise reported that the metal was a mixture and that it had not come out of the sand rock. This was another damper on the silver excitement. Martin, like Short, lost confidence in the silver situation.

However, Duvall kept “running” out the metal with his crucibles and iron ladle. On one occasion Duvall made a big “run” in an iron kettle over a wood fire. He extracted about five pounds of “silver.” Nevertheless, doubt and distrust increased about Duvall's sincerity.

He was accused of being a fakir and a fraud. After Duvall had made his five-pound “run,” Vickers, who frequently prospected in Silver Hills, took Duvall's five-pound “run” and some of the blue sandstone silver ore, saying he would take them to New York and have them assayed there. Vickers left, but returned in about a month. He reported that the New York chemist, like all the other professional chemists, pronounced the “silver” a mixture of metals, and said that it had not come out of the sand rock. He explained that they rolled the metal into sheets for him. These he exhibited, and gave to all those who were interested in the silver question a small sheet of what looked very much like tinfoil, which it probably was. Vickers left Silver Hills and was never seen in that neighborhood again. It was afterward claimed that he did not take the metal and ore any farther than his home in McLean County.

Duvall proposed to the people that if they would construct a furnace he would show them that he was no fakir. So the neighbors joined in and built a small furnace near his tanyard. It was only nine feet high, and therefore a great deal smaller than Buckner's iron furnace on Pond Creek. When the silver furnace was finished and ready for action the neighbors gathered to see the silver “run.” Duvall was watched very closely.

After the smelter had been in operation two days and very little metal had been obtained, Duvall declared the furnace had not been properly constructed. Men who had lost confidence in his work did not hesitate to tell him so to his face. This resulted in a fight at the furnace, and the place was abandoned. The stone oven stood for several years, and was always known as Duvall's Silver Stack.

About the time the furnace was abandoned, Duvall claimed he had received letters telling him that unless he left the county he would be killed. Duvall decided it would not be safe for him to remain in the county, and therefore left. However, he always insisted that the hills he had explored were full of silver and would be opened up some day. Just before he moved to Ohio County, he requested three men of the neighborhood to meet him at a certain place in Silver Hills. After they met, he led them to the head of a deep hollow and there dug up several pieces of metal, which he carried back home with him. No questions were asked by any one of these men, but their eyes were opened; the tale was told, and the silver excitement was soon over.

The secret of all this silver excitement, which lasted for about two years, was well planned and manipulated by Mark Duvall, for what purpose no one can tell, unless it was to sell his father's land at a high price.

In the early history of the county, pewter utensils were used for domestic purposes. Pewter bowls, plates, pans, etc., of the early days had gone out of use at this period. The best quality of pewter - called also “white metal” - was made of tin hardened with copper. The cheap grade was made of lead, alloyed with antimony and bismuth. Duvall had secured some of these old pewter vessels, cut them up, and hidden them away for use in working the silver trick. Duvall was aware of the fact that his neighbors knew nothing about ores of any kind. He made his “silver runs” in his iron ladle on a wood fire, which in itself was absurd. He made these “silver runs” by dissolving a piece of pewter in acid. He would pour this solution on the hot crushed rock in the ladle. The acid would soon be consumed and the metal would remain in the ladle with the crushed rock, and when cooled off the metal would be formed into small shot and could be picked out. This would occur no matter what kind of rock might be used.

Mark Duvall moved to Ohio County, where he studied medicine and lived to a good old age, but as far as is known he never “discovered” any silver in that county.

Source: Martin, Richard T. “Duvall's Discovery of ‘Silver Ore.’” Record [Greenville, KY], 30 Mar 1911.

Transcribed by Barry Duvall, 16 Mar 2013 and posted to the Muhlenberg County Kentucky History Group on Facebook.

Updated July 14, 2022