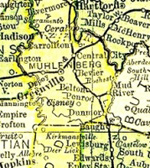

Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History: F

Buckner & Airdrie Iron Furnaces

Aylette H. Buckner, father of General Simon Bolivar Buckner, after operating a small furnace near his home Glen Lily, on the banks of Green River in Hart County (1), moved to Muhlenberg County where there was an extensive bed of iron ore and a plentiful supply of timber. With Cadwalader Churchill he formed a large company and built the furnace stack (1837) near the junction of Pond Creek and Salt Lick Creek, five miles south of Greenville (2). Before the end of the following year, operations had begun for the manufacture of iron. This furnace was variously known as the “Henry Clay Iron Works,” (3) Buckner's Stack, and Buckner & Churchill's Furnace.

A gristmill was built near the stack, numerous cabins were erected for the white and slave laborers, and a small, almost self-sufficient village grew up around the furnace.

Despite the great abundance of ore and timber, the company began to have financial troubles by the time it fairly got into business. The venture was on too large a scale for a remote region in the pioneer days. The great expense of getting ore to the stack, of burning charcoal, of finding markets, and strong competition from other sections in Kentucky more favorably situated, caused the Buckner & Churchill Company to fail financially; the furnace was abandoned in the year 1842.

A more ambitious undertaking was the Airdrie Furnance, erected in the northeastern section of Muhlenberg County in 1855, on the banks of Green River, near the village of Paradise (4). Sir Robert S.C.A. Alexander, a Kentucky-born descendant of a wealthy, titled Scotch family, purchased 17,000 acres of heavily wooded land in this area where a large bed of iron ore had been discovered. Young Alexander brough over from his father's country a number of Scotch miners and furnance men to help him develop the Muhlenberg County area. Arriving late in the summer of 1854, they built houses and cottages for the workmen and erected a large, cylindrical iron-shell stack, 48 feet high resting on a 26-foot square stone base 20 feet high, together with a huge three-story sandstone building to house the machinery for the furnace blast and rolling mills. The whole establishment was modeled after the Scotch pattern.

Four or five unsuccessful attempts were made to run the furnace. The Scotch workmen were unfamiliar with Kentucky metallurgical practices; the ore required a different treatment from that found in Scotland. After spending over three hundred thousand dollars without being able to produce a single pound of saleable iron, “Lord Alexander” abandoned the project in disgust and retired to a large Bluegrass farm he had purchased in Woodford County (5). The town of Airdrie was short-lived; and in a few years all the houses, stores, and the settlement's two-story hotel were in ruins.

Notes

- Stickles, Arndt M. Simon Bolivar Buckner: Borderland Knight. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 1940, pp. 7-8.

- Rothert, Otto A. A History of Muhlenberg County. Louisville, KY: John P. Morton, 1913, p. 178.

- Collins, Lewis. Historical Sketches of Kentucky Maysville, KY: Collins & James, 1847, p. 472.

- Rothert, op. cit., p. 221.

- Rothert, op. cit., p. 226.

Source: Coleman, J. Winston. Old Kentucky Iron Furnaces. Reprinted from The Filson Club History Quarterly 31(3), July 1957, pp.11-12.

Updated July 14, 2022