Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History: H

The Bloody Trail of the Harpes

The Bloody Trail of the Harpes was a string of senseless, heinous killings that terrorized citizens in the late eighteenth century on the frontier in Tennessee, Kentucky, and southern Illinois. Their killing career began about 1798 around Knoxville, Tennessee, and spread across Kentucky to the Cave-in-Rock, Illinois area as they littered their path with dead bodies. Micajah (Big Harpe) and Wiley (Little Harpe) were born in North Carolina about 1768 and 1770 respectively. Around 1795 the brothers with two women -- Susan and Betsy Roberts -- moved to Tennessee, lived amongst renegade Creek and Cherokee Indians, and practiced their skills of committing atrocities to a fine art of barbarity.

During a brief period of pretended respectability at a small area of land on Beaver Creek a few miles west of Knoxville, the Harpes engaged in horse stealing, hog stealing, and, evidently, barn and house burning. It was here that Wiley married Sarah Rice, a minister's daughter. Suspecting the Harpes, local citizens captured them, but they escaped. The next incident that became known was the disappearance of a man named Johnson whose body later appeared floating in the Holstein River; it is believed that the Harpes had ripped his body open to fill it with stones so it would not float. This was the beginning of their string of murders.

The Wilderness Road Murders marked the progress of the Harpes from Tennessee via western virginia to Kentucky in December 1798. Along this trail they are reputed to have killed a peddler named Peyton, the first killing in Kentucky, two people from Maryland, and Stephen Langford, a young man of means from Virginia.

The Langford Murder alarmed the citizens of Lincoln County. Captain Joseph Ballenger led a posse in pursuit of the Harpes and the three women, captured them near Stanford, and jailed them. upon searching the Harpes' possessions, the authorities discovered shirts with Langford's initials and a large amount of money such as Langford used. Convinced of their guilt, the Stanford authorities sent the five-member group to Danville where they appeared before the Lincoln County Court of Quarter Sessions on January 4, 1799. After hearing testimony, the three judges of the court decided the five should stand trial for the murder of Thomas [sic] Langford in the District Court of Danville in April. On March 16 Big and Little Harpe escaped. Nevertheless, the trial of the three women began on April 15, although each had given birth during their captivity. The sympathy of the court, the belief that they were now free from the Harpes and could lead decent lives, and the avowed intention of the women to return to Tennessee prompted local citizens to contribute clothes, money, and a horse for their trip.

As the women started toward Tennessee ad had gone a few miles, they changed directions and proceeded down the Green River, presumably toward the Ohio River. Posing as widows, the women located in an area about eight miles south of Henderson. The Harpe brothers either joined them there and continued to Cave-in-Rock or joined them at Cave-in-Rock. Along the way to join the women, the Harpes left their trace as they killed John Trabue.

John Trabue, the thirteen year-old son of Colonel Daniel Trabue of columbia, had gone to a neighbor's house to borrow flour and seed beans. Although the dog that had gone with him returned to the house, the boy did not, and a search party failed to find him. He had disappeared. Accidentally discovered about two weeks late, the mutilated body was in a sinkhole with the seed beans but not the flour.

The Flying Horse was the last straw for the Cave-in-Rock gang. Even they could not stomach the Harpes' nonsensical killing. The incident of the flying horse took place after a successful raid on a flatboat traveling on the Ohio River. While the gang was busily celebrating and enjoying the produce of their robbery, the Harpes had been saving the sole survivor of the flatboat for the evening's entertainment. When the time was right, they took the man's clothes off, bound him to a blindfolded horse, and led him to the top of the cliff overlooking the cave, and frightened the animal to run over the edge of the cliff with the horrified man bound on its back; both were killed on the rocks below. Laughing at their mischief, the Harpes walked down to see if they had been a success; the outlaws of Cave-in-Rock were not amused and forced the Harpes and their women to leave. The assumption that the Harpes had left the Kentucky-Tennessee area proved incorrect.

Other killings marked their trail and bloodied the frontier landscape: Dooley in Metcalfe County; Stump on Barren River below Bowling Green; two or three people near the mouth of the Saline River close to Cave-in-Rock; a farmer named Bradbury in Roane County, Tennessee, in July; the son of Chesley Coffey a few miles from Knoxville on July 22; William Ballard, a few miles from Knoxville; James Brassell on July 29, near Brassell's Knob; John Tully in Clinton County, Kentucky; John Graves and his thirteen year-old son on Marrowbone Creek.

The Child Murders were particularly heinous and are somewhat disputed. As the Harpes continued in their travels through Logan County, they supposedly killed a little girl and boy; Big Harpe was also to have killed his own baby by smashing its head against a large maple tree (against a cave wall?) and then tossed its body into the woods. However, Otto A. Rothert, The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock (Cleveland, 1924) suggests that Big Harpe's son and daughter born to wives Betsy and Susan respectively were seen after this incident, which would indiciate that the murdered child would have to have been the daughter of Sarah, wife of Little Harpe. Edward Coffman, A Story of Logan County (Russellville, Ky., 1962) believes the child murder story originated from a fanciful story about the Harpes in T. Marshall Smith, Legends of the War of Independence and Early Settlements (Louisville, 1855). There is, Coffman asserts, proof only that the Harpe women were tried for murder in Russellville in 1799 and had lived in Logan County for three years, not that the Harpe brothers were ever in the county.

Two Methodist ministers in the summer of 1799 stopped at the James Thompkins home on Deer Creek not far from Steuben's Link, Manitou. After being invited to supper, Big Harpe, that is, the large “Methodist Minister”, said a long grace at the table. They then discussed the neighborhood, the availability of game, and Thompkins indicated that he did not have gunpowder. The large minister gave him a generous supply of powder. After bidding farewell, the Harpes headed toward Squire McBee's farm with the obvious intention of killing him for McBee was a justice of the peace. As they neared the house, McBee's dogs attacked them and chased them away.

Nursing their pride as well as perhaps some bites, the Harpes went about four more miles to the home of Moses Stegall, located about five miles east of Dixon. Stegall had gone to Robinson Lick to replenish his supply of salt and was absent. Mrs. Stegall had allowed Major William Love, a surveyor, to spend the night in the house. In order to sleep in the loft of the house, Love had to climb up a ladder on the outside of the cabin; when the Harpes arrived he was in bed.

Lacking a spare bedroom, Mrs. Stegall quartered the Harpes in the same loft bed with Love. During the night one of the brothers smashed Love's head with a hand ax and after descending from the loft to eat breakfast, they complained to Mrs. Stegall that Love snored during the night. Mrs. Stegall placed her infant in a cradle for the Harpes to rock it and keep it quiet while she prepared breakfast. The baby was quiet -- unusually quiet; the alarmed mother checked on the child to discover its throat cut ear-to-ear. The Harpes then killed the mother with the same butcher knife used to kill the baby. On this night of August 20-21 after setting fire to the house that became a funeral pyre for the murdered victims, the Harpes left and headed for Squire McBee's house. Hiding along the road, they suspected the Squire might see the fire and investigate; they intended to ambush him along the road. However, two other men -- Hudgens and Gilmore -- who stumbled into their trap met the deathly fate intended for McBee.

John Pyles and four men discovered the burning house, reported it to McBee, and McBee along with William Grissom investigated. When McBee and Grissom returned to McBee's house, Stegall arrived and heard for the first time the tragedy of his family and Love. The men who had gathered at McBee's house decided to end the Harpe menace at any cost.

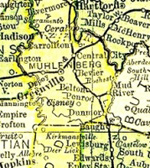

The Chase involved a posse of seven or eight backwoodsmen -- John Williams, Moses Stegall, John Leiper, Matthew Christian, Neville Lindsey, Silas McBee, William Grissom, James Thompkins -- who pursued and caught Big Harpe in Muhlenberg County at a place later known as Harpe's Hill. Details of the chase and Big Harpe's death vary; one accounty has Stegall cutting off the still live head of a dying Big Harpe to silence the possible ramblings of a repentent dying man whose revelations might have implicated Stegall in wrongdoings; yet another account suggests Stegall shot Big Harpe in the left side of his body in order not to destroy the head so it could be used as a trophy. The disposal of the body is also uncertain.

Harpe's Head, the final resting place for Big Harpe's head, is located about three miles north of Dixon where the highway from Henderson forks with one branch going to Marion and Eddyville and one branch going to Madisonville and Russellville. To transport the head some thirty-five miles from Harpe's Hill to Harpe's Head, the posse used a bag to carry it and also placed some roasting ears in the same bag -- “He won't eat them.” -- for their evening mean. Legend has it that ”Young Williams” would not eat that evening because the corn had been in the sack with the head. Stories vary as to how the head was positioned for display along the highway: in the forsk of a tree? on the sharpened end of a limb? upon the top of a lofty pole? on a tall young tree with its limbs trimmed? The comforting certainty is that Big Harpe was dead.

Little Harpe escaped to die by hanging on February 4, 1804, at Gallows Field, Jefferson County, Mississippi. As with Big Harpe's head, Little Harpe's head was displayed on a highway, the Natchez Trace, as a warning to other criminals. As the Natchez Trace widened with use and age, the road moved closer and closer to Little Harpe's grave until it was in a ditch. Little is left of the remains as dogs and other animals have disposed of the bones.

In regard to the wives, justices Samuel Hopkins and Abraham Landers examined the case against them on the charge of murdering Mrs. Stegall, the infant, James Stegall, and Love and sent them to Russellville for a grand jury investigation. The court cleared them and the Harpe women lived in Logan County for three years.

Upon hearing of these ghastly deeds, a petite elderly lady once commented, “They must have had a terrible childhood.” That is probably correct, for the Harpes were sons of a Tory sympathizer who fought for the British during the Revolutionary War. The neighbors in North Carolina hated British supporters and treated the Harpe children with hatred and contempt. This might, in part, explain their sociopathic behavior. But, there are many sons of many British supporters who did not turn to such behavior. No doubt a combination of complex conditions created what Richard H. Collins calls…&ldqou;the most brutal monsters of the human race”. The telling and re-telling of this story has given it permanence among frontier legends.

Additional Reading

The Harpe saga has a sizeable literature. The authoritative source is Otto A. Rothert, The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock (Cleveland, 1924). Richard H. Collins, History of Kentucky Vol. II (Frankfort, 1966) presents the accounts of Colonel James Davidson and the Honorable Joseph R. Underwood based on the recollections of contemporaries. Edmund L. Starling, History of Henderson County, Kentucky (Henderson, 1887) bases his account on Davidson and Underwood with some deviations such as the court records that show the examination of the Harpe women for the murder of Mrs. Stegall, James Stegall, and William Love. Edward Coffman, The Story of Logan County (Russellville, Ky., 1962) suggests that some Harpe legends lack proof. In the American Trails Series, Jonathan Daniels, The Devil's Backbone (New York, 1962) covers the Harpe story briefly and presents Little Harpe's assocations with the Mason gang.

The oldest written account is James Hall, Letters from the West: containing sketches of scenery, manners, and customs (London, 1828; reprinted, Gainesville, Fla., 1967). Another old version that originated or perpetuated legends is T. Marshall Smith, Legends of the War of Independence and of the Earlier Settlements in the West (Louisville, 1855).

A novelized Robert M. Coates, The Outlaw Years (New York, 1930) is based on Rothert's account as is W.C. Snively Jr., and Louanna Furbee, Satan's Ferryman (New York, 1968).

A modern “Harpe hunter,” Carl Veazey, “Murder on Deer Creek,” Sixth Annual Year Book published by the Historical Society of Hopkins County (Madisonville, Ky., 1980) adds new perspectives to the story by locating the exact site of the Stegall cabin and interviewing residents of the area and descendants of the posse that killed Big Harpe.

Source&58; Gooch, J.T. “The Bloody Trail of the Harpes.” The Pennyrile: history, stories, legends. Madisonville, KY: Madisonville Community College, 1982.

Presented with the kind permission of J.T. Gooch

Updated July 14, 2022