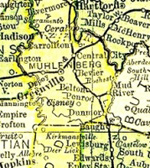

Muhlenberg County Kentucky

Local History

Tobacco's Early History in Greenville, Kentucky

William Martin was pioneer of the plug tobacco business in the Green River country

Greenville's tobacco in its course from plant bed to palate and pipe has found its way all over the world. From a limited demand in Muhlenberg County, its fame spread first over western Kentucky, then throughout the entire South; and now its leaf, manufactured plug, and pipe tobaccos are known everywhere. Tradition says that the first plant in Muhlenberg was raised in 1800.

Comparatively, few crops were grown until the latter part of the 1830s since which time tobacco has been one of the county's principal products.

William Martin, who came to Muhlenberg County in 1805 from Virginia, is the pioneer in the plug tobacco business in the Green River country and also among the first in the state of Kentucky. In the 1830s he laid the foundation of an industry that, since his time has developed and given to Greenville an international reputation as a tobacco raising, rebundling, and manufacturing point.

In the course of time, William Martin was followed by three of his sons, and they in turn by some of their sons, and so on down through four generations. In fact, most of the tobacco manufacturing in Muhlenberg has been done by some of his descendants. Since his day the name Martin has always been associated locally with the making of plug.

It was in 1835, in the Old Liberty neighborhood, six miles southwest of Greenville, that William Martin, a son of Thomas Martin, first manufactured plug. The tobacco raised in those days, it is said, was about the same kind of yellow prior and shoestring still grown in some parts of Muhlenberg. His son, Dabney, later introduced other varieties of the plant.

William selected the best leaf for his plug, using not only his own crop, but also those of his neighbors. Most of the tobacco then each year was manufactured into plug during the course of a few months. The rest he prized into hogsheads and shipped it to New Orleans. He had no modern appliances in his small manufacturing establishment. He simply stemmed and redried the leaf and pressed it into cakes. He packed the tobacco into forms or molds to which he applied pressure by pulling down on one end of a 20-foot beam, the other end of which was tenoned in a mortise cute for that purpose into one of the heavy timbers of his barn. After the beam or lever had been pulled down by all the available human muscle, it was held in position by means of a sword like hickory peg stuck into an auger hole in the wall. The pressure thus produced and held was so great that, according to tradition, “it not only made the juice fly,” but turned the tobacco into solid black cakes. These plugs usually weighed about eight ounces and were packed into boxes holding from 100 to 150 pounds.

William Martin followed this business only a few years; however, before he quit, one of his sons, William Campbell Martin, took up the same work and continued in it until about 1840.

In 1840 Dabney A. and Ellington W. Martin, two of the younger sons of William Martin, established a plant on North Main Street in Greenville and began the making of that brand known as “Greenville.” They were the first to use screws, and also the first to introduce flavoring and sweetening in plug. D.A. and E.W. Martin loaded their manufactured product on six mule wagons, each holding about 4,000 pounds, and started them on long trips into the South. These large wagons were usually accompanied by one or two smaller ones for the purpose of making side trips from the main road and the moving source of supply. They delivered their goods on consignment, that is, to be paid for when sold or to be returned when called for. There was so tax or internal revenue on tobacco in those days, and the manufactured plug usually sold for “two bits” or 25¢ a pound. Their collector called on the customers about every six months. The quality and demand for their brand was such that they were seldom obliged to take back unsold stock.

D.A. and E.W. Martin were the first men in Muhlenberg County to export the stemmed weed. As early as 1845 they added a stemmery to their plug factory. The plug and the strip business were both a success and resulted in the accumulation of a fortune. Most of their plug trade was in the South. After the Civil War began, they were unable to collect any bills. Futhermore, much of their tobacco was confiscated, and all their slaves set free. The combined effect of these reverses was almost disastrous to them, but they continued their business until shortly after the close of the war.

In 1869 they sold their building and machinery on North Main Street to Hugh N. Martin, who, as before stated, was one of the sons of the original William Martin. H.N. Martin manufactured in the same building for a few years, and then removed his plant to Chestnut Street, where, in 1875, he added a stemmery and began putting in strips for the English market. In 1899 he removed to Louisville, in which city he conducts a leaf rehandling establishment.

Such is a brief outline of the industrial history of the first tobacco manufacturing business from its beginning down to present. In the meantime, other men went into the business. In the early 1840s George Short began the manufacture of plug on North Main Street, near where D.A. and E.W. Martin later located. Short operated until about 1860. Several years after his death, his place was converted into a rehandling house and remained such until its destruction by fire.

About the year 1874, Ezekiel Rice, a grandnephew of William Martin, opened a plug factory in the building, then recently vacated by H.N. Martin on North Main Street. He also rehandled leaf and put up a few strips. In 1899 he removed to Louisville, and one year later sold out to the American Tobacco Company.

During the latter part of the 1870s, R.T. or “Dick” Martin, a son of Thomas I. Martin and therefore a grandson of the original William Martin, began the manufacture of plug. In 1902 he sold his machinery and brands to a company in Hopkinsville, to which city the plant was then moved.

All the men who bought tobacco in Greenville did not drift into the plug manufacturing business. Among the outsiders who put up leaf and strips were Fattman & Company and Ackenberger & Company of New York. Fattman handled tobacco in Greenville form 1863 to 1870. Ackenberger, whose local representative was Ed Reno, bought tobacco in Greenville for a few years in the 1870s.

Tom Summers, the father-in-law of Rufus Martin, bought leaf from about 1830 to 1870. He was one of the leading tobacco men of his day. Felix Martin, a son of Hutson Martin, was among the buyers from 1880 to 1885 and so was Geroge Eaves. Rufus Martin, a son of Felix Martin and therefore a grandnephew of the original William Martin, began the leaf and strip business in the early 1880s and conducted a large house up to the time of his death in 1903.

Up to about 15 years ago, some of the farmers who raised tobacco would occasionally buy the crops of a few of their neighbors. This they prized into hogsheads which were sent to Louisville and sold. Among such buyers and shippers were William Y. Newman, Tom B. Johnson, J. Lyles, Albert Miles, C. Cisney, and Alney E. Newman.

There were, of course, other tobacconists in and around Greenville, but their careers, like some of those to which I have referred, are subjects for a sketch of more recent times.

Let us not forget that while the manufacturers and rehandlers in Greenville were engaged in disposing of the homegrown tobacco, the farmers scattered over the adjoining country were busy raising more of the weed. The growing of tobacco meant hard labor in the olden times, and it means hard labor now. No crop requires more care and greater patience than tobacco. From the sowing of the seed to the hauling of the product to the market, every stage requires its own particular kind of weather. Should one of these ungovernable conditions fail to prevail at the right time, the quantity and quality of the tobacco are seriously affected. In fact, the uncertainty of the outcome has always made it somewhat of a “gambling game.” Tobacco today, as in the early years, is the source of much worry, watching, and waiting. It usually represents a tenant's toil, for, as a rule, it is a cropper's crop.

A crop now, as in the past, demands constant attention for “13 months out of the year.” The outdoor work begins with the burning, sowing, and covering of the plant bed, and continues down through the breaking of the ground, making the hills, setting, and sometimes resetting the plants; then the hoeing and plowing, priming, top plug, suckering, worming, and cutting, and ends in the housing. After it is hung in the tobacco barn, the firing and curing are followed by the stripping, sorting, tying, rehandling, and bulking.

The curing of tobacco by firing was introduced by the raisers of the first leaf, but it was not universally practiced here until about 1830. Although firing is the most disagreeable and hazardous part of the management of the crop, it, like all the other barn work, nevertheless, usually results in a pleasant time. On that occasion, card playing, potato roasting, storytelling, and the playing of pranks take place around the smoling and slowly burning logs until long after the midnight hour. In fact, a jovial spirit generally prevails during all the indoor work, especially at the stripping. Old traditions are then recalled, the latest happenings discussed, new stories introduced, and many of the old jokes and tales retold. Among the latter are a number that have the reputation of being “as old as the hills.”

One of them is to the effect that Grandfather Somebody had a calf trained, so that when he turned it into his tobacco patch it nipped off the tops of all the plants, and then spared the farmer the trouble of topping. Another is that Uncle So-and-So had worms as large as the largest watermelons and could not get rid of them in any other way than by shooting them. At one time, so the tale is told, worms were so bad that the children could not go to school; not because they might be needed at home to help pick the pests or kill the “green hail” but because the worms might attack pupils on the road. The punster never fails to say that Old Man Somebody set out tobacco plants is his day until he became stooped.

In spite of the constant work, unfavorable worry, and frequent disappointments, the handling of tobacco has always had its many pleasant features in the field as well as in the barn. Not the least among these features is watching the green leaves turn into greenbacks.

The history of every crop is a combination of tragedy, romance, and comedy. Each crop grown since the first introduction of tobacco is part of the history of every Muhlenberg farm and farmer. The story of Greenville's tobacco men and tobacco houses is closely interwoven with the history of the growth and development of the town.

Source: Kentucky Explorer, 23(6), Nov 2008, pp. 42-45.

Updated July 14, 2022