Muhlenberg County Kentucky

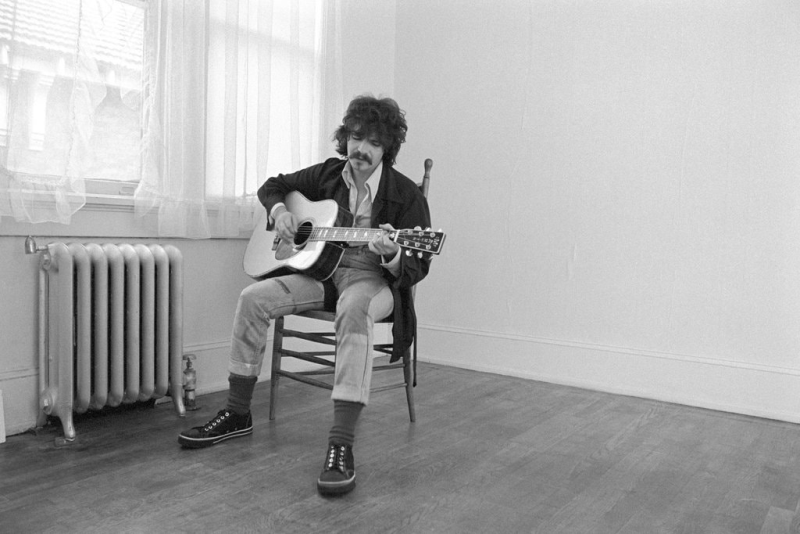

John Prine

John Prine, Who Chronicled the Human Condition in Song, Dies at 73

A singer and songwriter with a raspy voice and a gift for offbeat humor, he was revered by his peers, including Bob Dylan. He died of the coronavirus.

By William Grives. Published 7 Apr 2020. Updated 16 Apr 2020. Caryn Ganz & Neil Vigdor contributed reporting.

John Prine, the raspy-voiced country-folk singer whose ingenious lyrics to songs by turns poignant, angry and comic made him a favorite of Bob Dylan, Kris Kristofferson and others, died on Tuesday in Nashville. He was 73.

The cause was complications of the coronavirus, his family said.

Mr. Prine underwent cancer surgery in 1998 to remove a tumor in his neck identified as squamous cell cancer, which had damaged his vocal cords. In 2013, he had part of one lung removed to treat lung cancer. He had been hospitalized since late last month.

Mr. Prine was a relative unknown in 1970 when Mr. Kristofferson heard him play one night at a Chicago club called the Earl of Old Town, dragged there by the singer-songwriter Steve Goodman. Mr. Kristofferson was performing in Chicago at the time at the Quiet Knight. Mr. Prine treated him to a brief after-hours performance of material that, Mr. Kristofferson later wrote, “was unlike anything I&339;d heard before.”

A few weeks later, when Mr. Prine was in New York, Mr. Kristofferson invited him onstage at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village, where he was appearing with Carly Simon, and introduced him to the audience.

“No way somebody this young can be writing so heavy,” he said. “John Prine is so good, we may have to break his thumbs.”

The record executive Jerry Wexler, who was in the audience, signed Mr. Prine to a contract with Atlantic Records the next day.

Music writers at the time were eager to crown a successor to Mr. Dylan, and Mr. Prine, with his nasal, sandpapery voice and literate way with a song, came ready to order. His debut album, called simply “John Prine” and released in 1971, included songs that became his signatures. Some gained wider fame after being recorded by other artists.

They included “Sam Stone,” about a drug-addicted war veteran (with the unforgettable refrain “There&39;s a hole in Daddy's arm where all the money goes”); “Hello in There,” a heart-rending evocation of old age and loneliness; and “Angel From Montgomery,” the hard-luck lament of a middle-aged woman dreaming about a better life, later made famous by Bonnie Raitt.

“He's a true folk singer in the best folk tradition, cutting right to the heart of things, as pure and simple as rain,” Ms. Raitt told Rolling Stone in 1992.

Mr. Dylan, listing his favorite songwriters in a 2009 interview, put Mr. Prine front and center. “Prine's stuff is pure Proustian existentialism,” he said. “Midwestern mind trips to the nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs.”

John Prine was born on Oct. 10, 1946, in Maywood, Ill., a working-class suburb of Chicago, to William and Verna (Hamm) Prine. His father, a tool-and-die maker at the American Can Company, and his mother had moved from the coal town of Paradise, Ky., in the 1930s.

Mr. Prine later wrote a ruefully bitter song titled “Paradise,” in which he sang:

The coal company came with the world's largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land

Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man

John grew up in a country music-loving family. He learned guitar as a young teenager from his grandfather and brother and began writing songs.

After graduating from high school, he worked for the Post Office for two years before being drafted into the Army, which sent him to West Germany in charge of the motor pool at his base. After being discharged, he resumed his mail route, in and around his hometown, composing songs in his head.

“I always likened the mail route to a library with no books,” he wrote on his website. “I passed the time each day making up these little ditties.”

Reluctantly, he took the stage for the first time at an open-mic night at a small Chicago club called the Fifth Peg, where his performance met with profound silence from the audience. “They just sat there,” Mr. Prine later wrote. “They didn't even applaud, they just looked at me.”

Then the clapping began. “It was like I found out all of a sudden that I could communicate deep feelings and emotions,” he wrote. “And to find that out all at once was amazing.”

Not long after, Roger Ebert, the film critic for The Chicago Sun-Times, wandered into the club while Mr. Prine was performing. He liked what he heard and wrote Mr. Prine's first review, under the headline “Singing Mailman Who Delivers a Powerful Message in a Few Words.”

“He appears onstage with such modesty he almost seems to be backing into the spotlight,” Mr. Ebert wrote. “He sings rather quietly, and his guitar work is good, but he doesn't show off. He starts slow. But after a song or two, even the drunks in the room begin to listen to his lyrics. And then he has you.”

Mr. Prine had a particular gift for offbeat humor, reflected in songs like “Jesus, the Missing Years,” “Some Humans Ain’t Human,” “Sabu Visits the Twin Cities Alone” and the antiwar screed “Your Flag Decal Won't Get You Into Heaven Anymore.”

“I guess what I always found funny was the human condition,” he told the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph in 2013. “There is a certain comedy and pathos to trouble and accidents.”

After recording several albums for Atlantic and Asylum, he started his own label, Oh Boy Records, in 1984. He never had a hit record, but he commanded a loyal audience that ensured steady if modest sales for his albums and a durable concert career.

In 1992, his album “The Missing Years,” with guest appearances by Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty and other artists, won a Grammy Award for best contemporary folk recording. He received a second Grammy in the same category in 2006 for the album “Fair and Square.&rquo;

Mr. Prine, who lived in Nashville, was divorced twice. He is survived by his wife, Fiona Whelan Prine, a native of Ireland whom he married in 1996; three sons, Jody, Jack and Tommy; two brothers, Dave and Billy; and three grandchildren.

In 2017, Mr. Prine published “John Prine Beyond Words,” a collection of lyrics, guitar chords, commentary and photographs from his own archive.

In 2019, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and his album “Tree of Forgiveness” was nominated for a Grammy for best Americana album. It was his 19th album and his first of original material in more than a decade. (The award went to Brandi Carlile, for “By the Way, I Forgive You.”)

Mr. Prine went on tour in 2018 to promote “Tree of Forgiveness,” and after a two-night stand at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville - known there as the mother church of country music - Margaret Renkl, a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times, wrote, under the headline “American Oracle”:

“The mother church of country music, where the seats are scratched-up pews and the windows are stained glass, is the place where the new John Prine - older now, scarred by cancer surgeries, his voice deeper and full of gravel - is most clearly still the old John Prine: mischievous, delighting in tomfoolery, but also worried about the world.”

In December, he was chosen to receive a 2020 Grammy for lifetime achievement.

As a songwriter, Mr. Prine was prolific and quick. In the early days, he would sometimes dash off a song while driving to a club.

“Sometimes, the best ones come together at the exact same time, and it takes about as long to write it as it does to sing it,” he told the poet Ted Kooser in an interview at the Library of Congress in 2005. “They come along like a dream or something, and you just got to hurry up and respond to it, because if you mess around, the song is liable to pass you by.”

Source: Grimes, William. “John Prine, Who Chronicled the Human Condition in Song, Dies at 73.” The New York Times, 16 Apr 2020. Retrieved 30 Apr 2020, nytimes.com.

Updated July 17, 2022